There would be no Michigan Football or Athletic Tradition were it not for Fielding Yost!

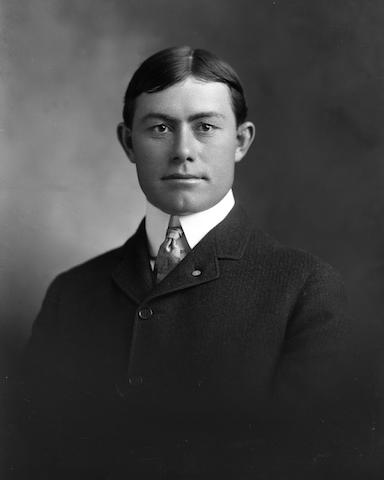

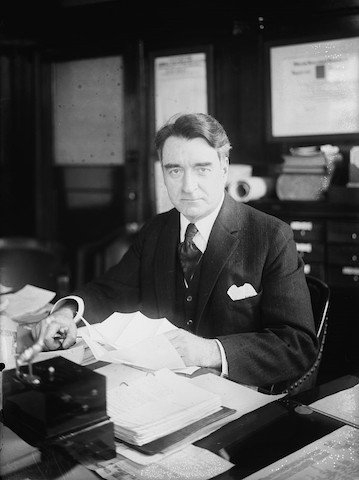

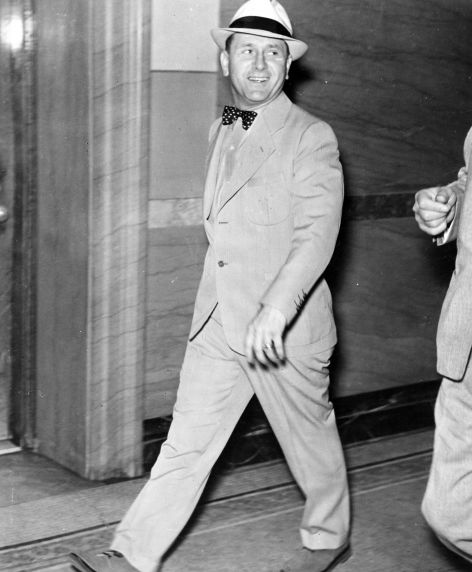

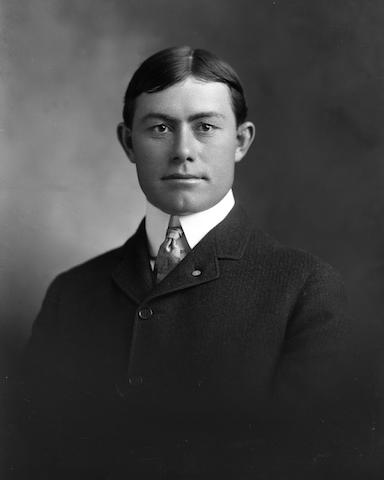

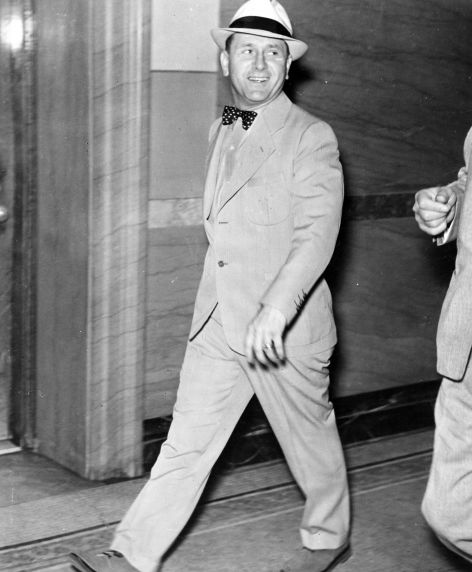

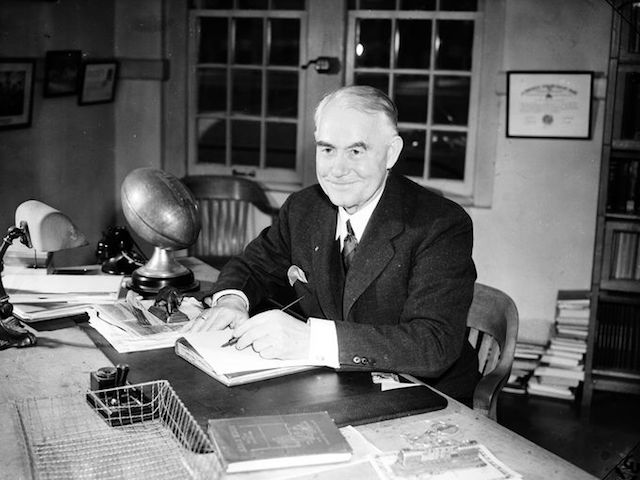

Fielding Yost in 1938

Fielding Yost was hired by Athletic Director, Charles Baird, in 1901 at the age of 30 for one purpose: To Coach Football. Yost set a standard of excellence in Ann Arbor that has been unmatched, 1901-1905, with a 56 game unbeaten streak outscoring opponents, 2,821 to 42. Keene Fitzpatrick was his only assistant and team trainer; he worked at Michigan, 1894-1910, before moving on the Princeton, 1910-1934. Yost won 6 National Championships and 10 Conference Championships; Yost had 165 wins at Michigan with a winning percentage of 83.33%, and an incredible 119 shutouts over his Wolverine coaching career; these achievements set a standard at Michigan that has not been achieved by any coach nor any athletic director since Yost retired as Head Football Coach in 1926, and Athletic Director in 1941. Abner Howell, a negro, was a member of his 1902-1904 squads. Jerry Knowlton, Law Professor, was the Faculty Representative, 1896-1917.

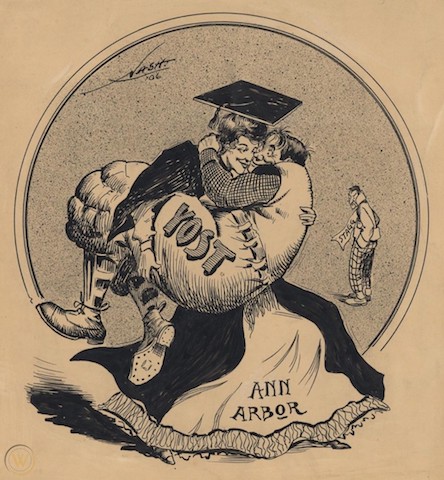

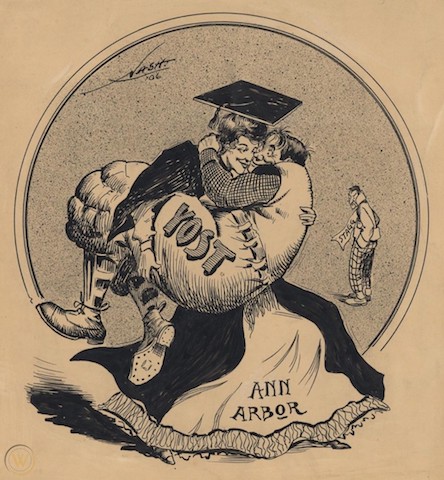

Yost in 1901 and Cartoon showing Ann Arbor's Love Affair with Yost in 1905

There were 80 college football teams competing when Yost was hired in 1901; the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States (IAAUS) was founded on March 31, 1906 with 39 member schools; it was renamed the NCAA in 1910 with 76 members, and grew to 150 members by 1931. Former Three-Time Michigan Football Captain, Horace Prettyman, 1882-1890, and Ann Arbor High School graduate, started a boarding house and training table in 1887 that supported the football team on North University St. until 1914; Prettyman served as an Ann Arbor City Councilman, 1891-1895, and Washtenaw County Supervisor in 1901.

Prettyman's Training Table in 1904 and Boarding House in 1906 on North University

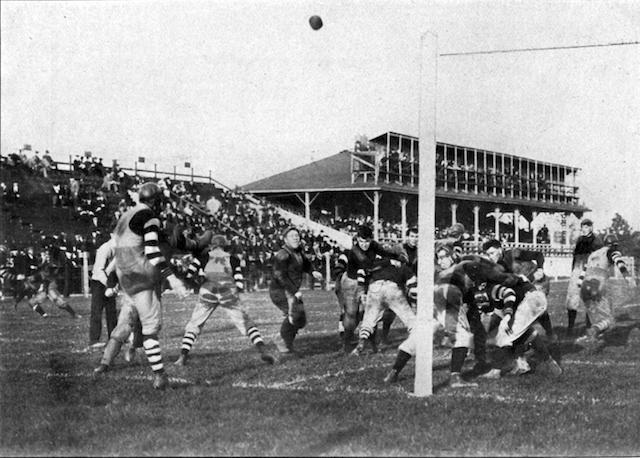

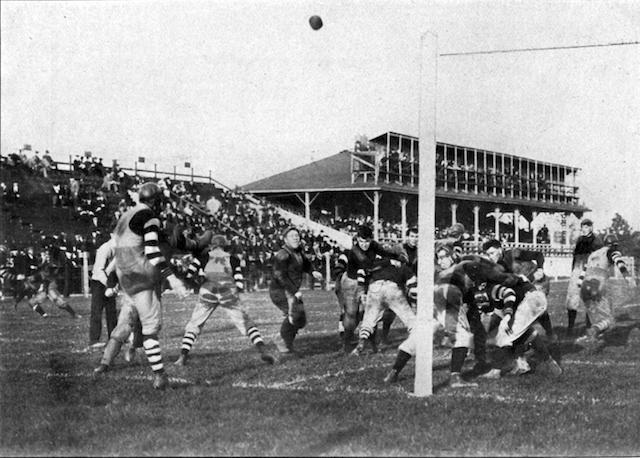

Michigan Football in 1905

In Yost’s era of coaching football starting in 1901, the University of Michigan had an enrollment of 3,712 men at the eight colleges: Literature, Science and Arts, Law, Engineering, Medical, Dental, Pharmacy, Music, and Nursing Schools. Over 300 men tried out annually for 13 varsity spots on the football team with an additional 38 reserves; in the 1904-05 school year, there were 765 men enrolled in LSA and 310 men in the Medical School. There were 51 players photographed in a 1901 team photo. In that era, a coach could not recruit players, but only develop athletes within the student body; there were no scholarships, but a coach could help an athlete find a job plus room & board to support their college expenses. Roster sizes were slow to expand, and travel teams were even smaller; Michigan only took 26 players to Columbus for their 1918 game and 33 players for their 1924 game, for example. Roster sizes were increased to 40 players by the late 1920s after Yost finished his coaching career. This is far different from football today where Division I schools have rosters of 120 players, and 85 have full scholarships with travel rosters of 75 players.

Ferry Field in 1907

In 1869, only 2% of Americans attended college; by 1940, that number had increased to 9%, and that is a drastic difference from the 72% of Americans that attend college in 2020. In 1900, there was only 30% of the negro population in America that even attended primary educational institutions, K-12; that number increased to 65% by 1940. The number of negro students attending colleges or universities was significantly less. Many children, 1900-1940, didn’t even attend secondary school as they were needed to work on their farms and/or participate in child care for siblings; only 10% of 14-17 year-olds attended secondary schools in 1900, and by 1940 it rose to 70%. Average annual expenses for students were $400 per year when Yost arrived in 1901, and rose to $600 per year, 1920-1940. In 1912, there were 39 negro students at the University of Michigan; by 1925, there were 60 negro students at the University of Michigan with an enrollment of over 10,000, and by 1931, there were 61 negro students enrolled. The University embraced foreign students with Barbour scholarships while doing little for negro students enrolled; there were 160 Chinese students enrolled in the 1935-36 school year, and 288 foreign students enrolled Fall, 1935 from 58 countries. Raleigh Nelson was appointed as university counselor for foreign students in 1933; he organized a special Thanksgiving dinner with over 400 foreign students participating in 1940. Negro students has no counselor nor any special event held in their honor. Joseph Leon Langhorne, a negro graduate in 1928, stated, “The colored were not part and parcel of the school.” If there were more negro students with athletic ability available, one can best believe that Yost would have welcomed him to his football program. As a highly competitive leader, Yost wanted to best players available to help his teams win.

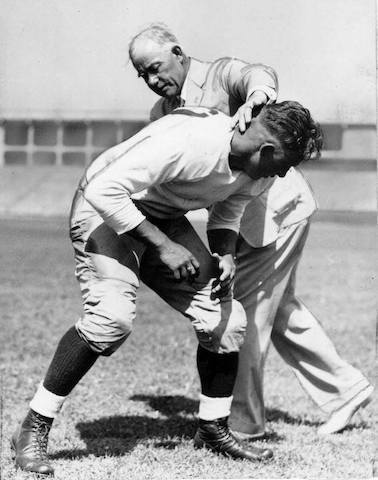

Yost and Fitzpatrick coaching in 1904

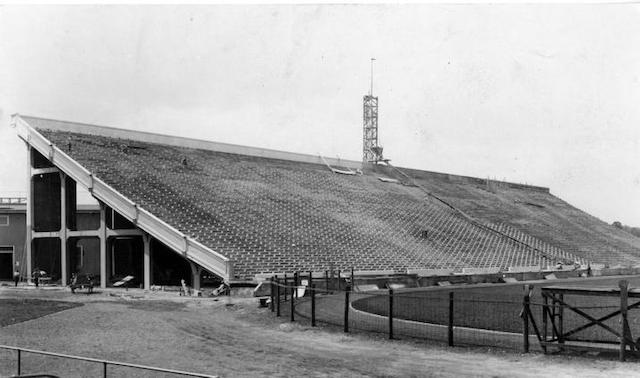

There were only four varsity sports when Yost arrived in Ann Arbor in 1901: Baseball (1865), Football (1879), Tennis (1892), and Track (1895). Home football games were played at Regents Field, 1893-1905, with a seating capacity of 800; there were only 3500 fans who could stand or sit at the games at Regents Field in 1901. It was renamed as Ferry Field in 1902 after additional land was donated by seed baron, Dexter Ferry; Lorenzo Thomas was its groundskeeper. Ferry Field was rebuilt in 1906 with a seating capacity of 1800, concrete stands were added by 1914 increasing the seating capacity by 25,000, and the it grew to 46,000 by the time the final game was played there in 1926. Michigan’s record at Ferry Field was 88-14-2.

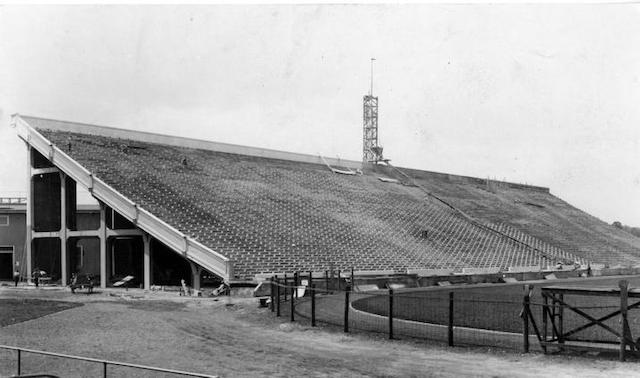

Ferry Field Concrete Stands in 1914

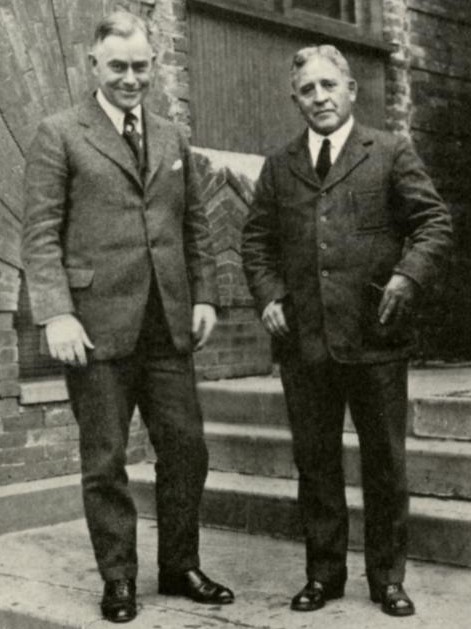

Yost with Stagg in 1921 following a track meet

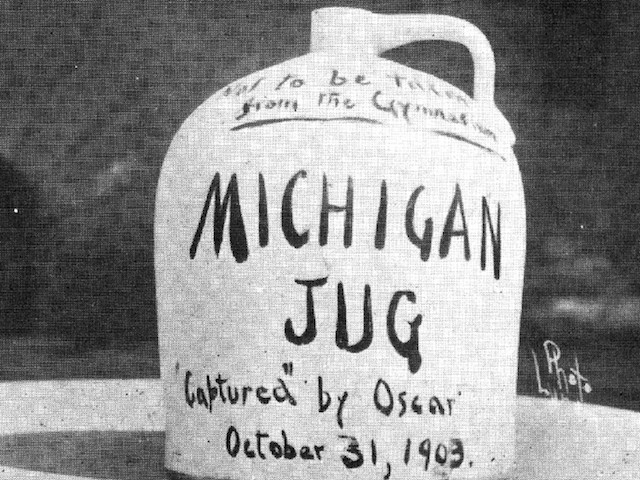

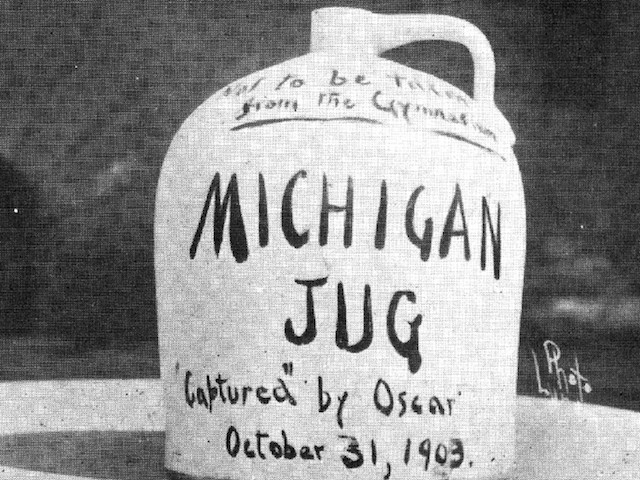

Michigan’s first and only rival in 1901 was the University of Chicago who was coached by Amos Alonzo Stagg, 1892-1940; the rivalry began in 1892, and Yost increased its intensity by defeating Stagg handily in their first four meetings, 1901-1904. Yost added the highly competitive rivalries of Minnesota with the Little Brown Jug rivalry in 1903, the first Trophy game in college football; he also initiated and escalated rivalries with Michigan State after a 119-0 shellacking in 1902, and Ohio State with a 86-0 trouncing in 1902 plus shut outs in six of their first seven meetings. Other important rivalries in that Yost’s early coaching era included Illinois, Notre Dame, Cornell, and Pennsylvania. Yost established his Summer Training Camp at Whitmore Lake in 1902.

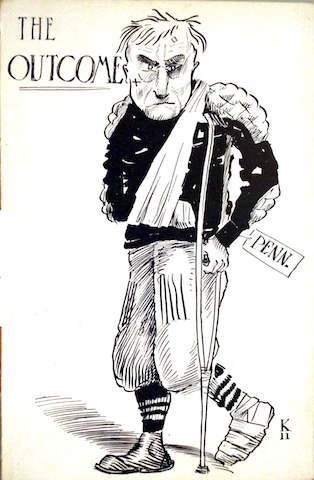

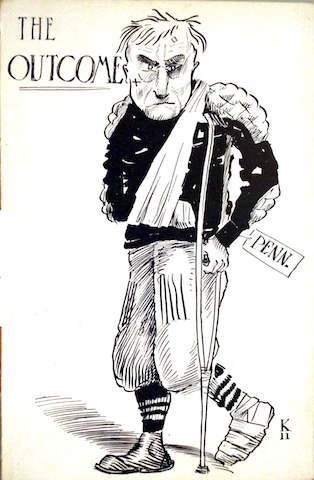

Michigan-Pennsylvania Cartoon in 1911 and Little Brown Jug in 1903

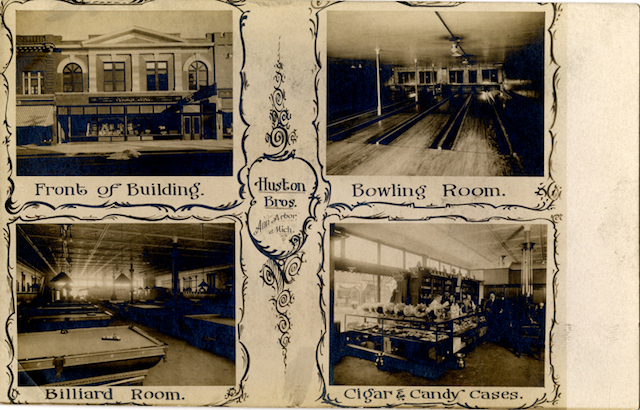

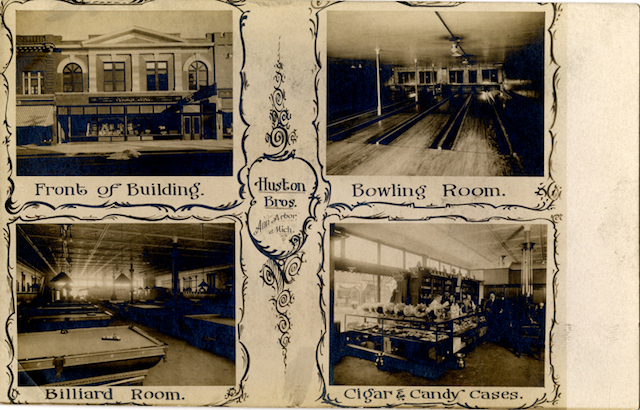

The Huston brothers, Roscoe and Cy, operated billiards, bowling alleys and boarding rooms in four locations near the campus; both graduated from the University of Michigan in 1900 and 1902; later, they established the Detroit Recreation Building in 1917 at 212 West Lafayette with four floors of bowling (88 lanes) and 103 billiard tables. These venues were hangouts for many men where gambling, business affairs and politics were all forms of entertainment.

Huston Brothers locations in Ann Arbor and their Detroit Recreation Building

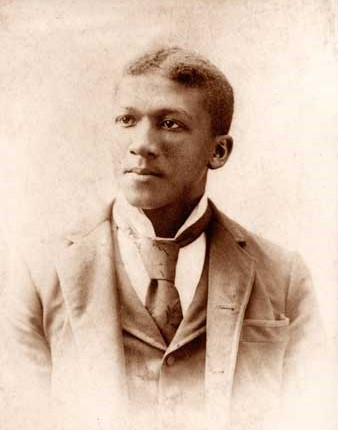

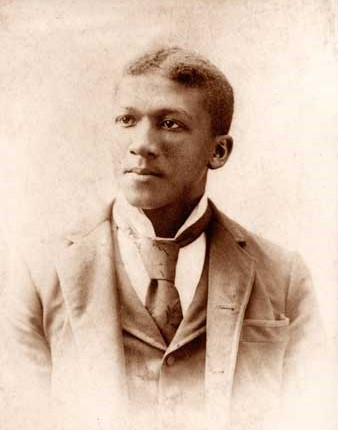

George Jewett in 1895

There had only been one negro football player at Michigan prior to Yost’s arrival, George Jewett in 1890-1892; Jewett was valedictorian at Ann Arbor High School, spoke three foreign languages fluently (German, French and Italian), and played 2nd base on the Wolverine baseball squad after being the Captain of his high school football, baseball, and debate teams. Jewett transferred to Northwestern after a conflict with Medical School Dean, Victor Vaughn, 1891-1921; Vaughn was a noted proponent of eugenics, and came to Ann Arbor from Missouri, a state in the confederacy, and Vaughn's father was nearly killed by Union Soldiers. The Victor Vaughn Dormitory was built in 1938; it was segregated when first opened. Jewett graduated from Medical School there, and later came back to Ann Arbor in 1899, got married in 1901,and opened a dry cleaning and pressing business, The Valet, on State Street next to the First Congregational Church between Newberry Hall until he passed away at the age of 38.

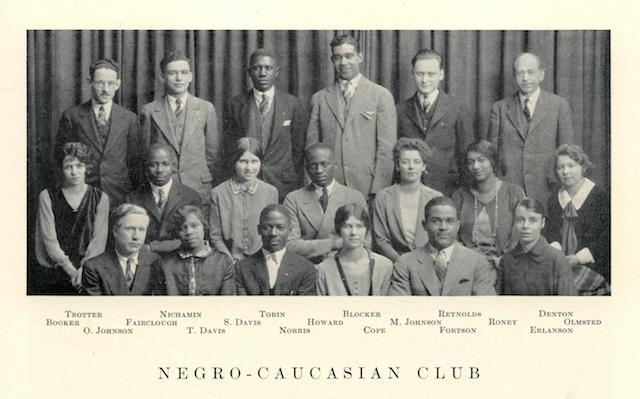

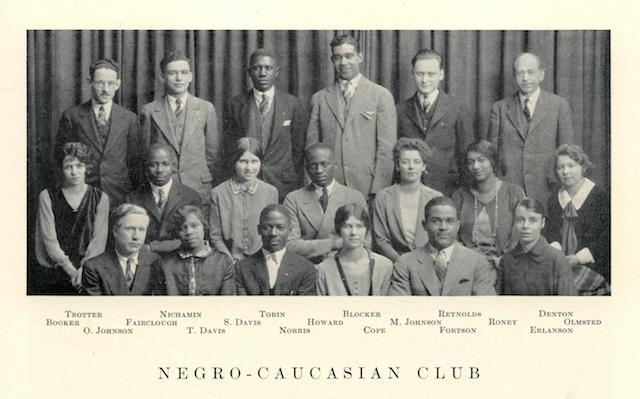

Negro-Caucastian Club in 1926

Since there were few negroes admitted to the University of Michigan, the first negro fraternity, Alpha Phi Alpha, began in 1909, and grew to 25 members by 1928; there were 34 Literary and Professional Fraternities, but only 8 sororities on campus in 1900. A second negro fraternity was established in 1922, Omega Psi Phi. In 1902, the Colored Students Club was established, but didn’t last long; later, in 1920, the Negro-Caucasian Club was introduced at the University of Michigan with Oakley Johnson as its Advisor. The club was forced to drop its purpose of working “for the abolition of discrimination against negroes.” The club brought in Civil Rights Leaders to speak on campus: Alain LeRoy Locke, W.B.E. DuBois, Jean Toomer, A. Philip Randolph, Frank Murphy, and Clarence Darrow to speak at the University of Michigan. Darrow defended Detroit Physician, Ossian Sweet in the most celebrated Civil Rights trial of the era.

Alpha Phi Alpha

The club disbanded by 1930 after expanding to 60 members in 1927. The Michigan Socialist House began in 1932 at 335 East Ann St.; it was the first integrated house on campus for men’s housing; similarly, the Lester House at 909 East University was initiated in 1940 for integrated women’s housing. The Student Lecture Association was formed in 1854; they brought in a bevy of nationally and internationally known speakers broaching many ethical and moral subjects including abolitionism (Theodore Tilton, Anna Dickinson, and Wendell Phillips) and Darwinism (Louis Agazziz); they ceased to exist by 1912. There were many famous lecturers who spoke on controversial subjects at University Hall, Hill Opera House and the Whitney Theater.

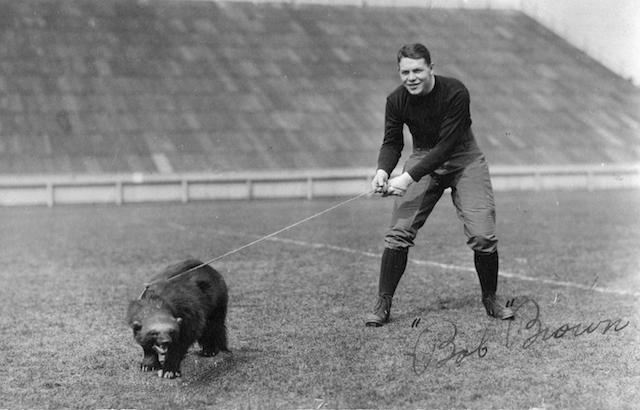

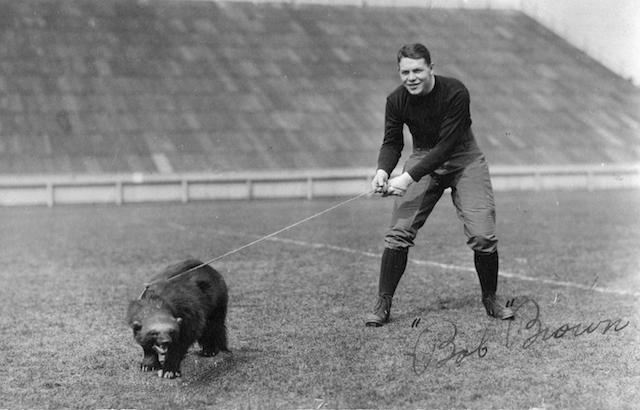

John Behee, Author of Hail to the Victors and Coach Yost--Michigan Football Captain Bob Brown and a Wolverine Mascot in 1925

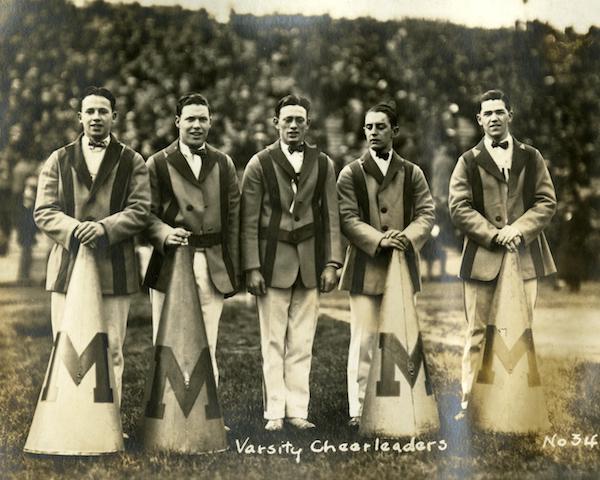

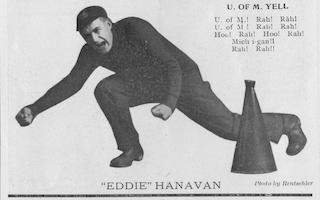

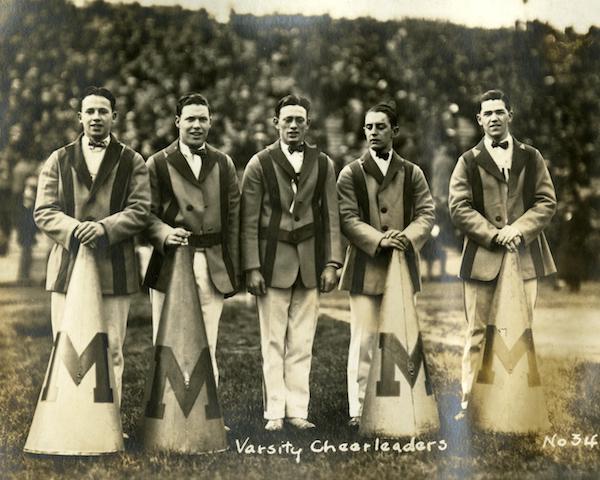

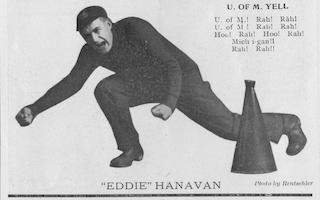

John Behee, author of Hail to the Victors in 1974 with ground-breaking research into the history of African-American athletes at the University of Michigan and Coach Yost in 2020, articulated, Yost was “responsible for initiating and building the unique school spirit” in Ann Arbor. In 1901, he began with a child, Jerome, as the team mascot. Yost authorized the practice of “yellers” at his football games in 1903; yell squads began at other colleges as early as 1883. Cap Night was first celebrated in 1904; songs were sung and speeches were made, and freshman burned their caps as a symbol of graduating from the ranks of "first year men." The “Block M” was instituted on November 16, 1907 against Pennsylvania; he also innovated a different team mascot that year, a coyote. Male cheerleaders were launched in 1923 with three men, and grew to nine men to 1929.

Block M in 1910 and Michigan Cheerleaders in 1923

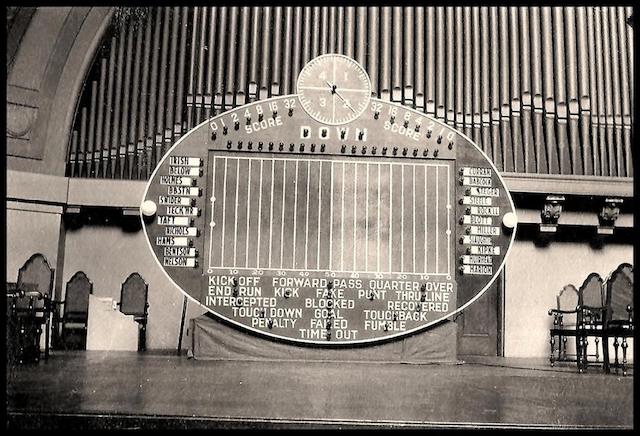

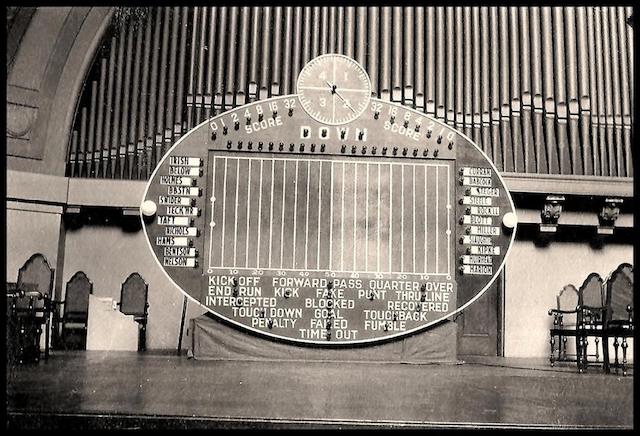

When radio broadcasts of Michigan Football games began in 1924, the Grid Graph was set up at Hill Auditorium to follow the progress of away games; the student, staff and alumni interest in Michigan Football skyrocketed and became an addiction for many fans. Yost brought in Wolverines, Biff and Bennie, to Michigan Stadium in 1927. Football games at Michigan Stadium became city events that boosted the economy, and the pageantry changed Ann Arbor into the finest college town in America. When the University of Michigan Zoo was built in 1929; a Wolverine was brought in until 1950 when it passed away; the facility was closed in 1962. The Mud Bowl Tradition began in 1934 between fraternities, Alpha Sigma Epsilon and Phi Delta Theta at the corner of Washtenaw and South University. Yost built enthusiasm and excitement in not only the football team, but the entire athletic programs at Michigan; he also created teamwork between coaches, the athletic department, the student body, staff, and alumni over his 40 years of service.

Grid Graph in 1923 and Eddie Hanavan, Master Yeller in 1911

David Starr Jordan, Stanford President, 1891-1913, and former University of Indiana President, 1884-1891, accused Yost of “professionalism” November, 1905; this was an effort of revenge on his part after Yost left Stanford after coaching there one season in 1900, and Michigan’s humiliating 49-0 victory over the Cardinal in the 1902 Rose Bowl. Jordan later attacked George “Dad” Gregory who came with Yost to Ann Arbor in 1907. Jordan, a known eugenicist, had his name removed from buildings at Stanford in 2020.

Fielding and Eunice Yost in 1924

Yost married Eunice in 1906, and their son, Fielding Jr. was born in 1910; they were members of the First United Methodist Church at the corner of State and Huron. They resided at 548 and 424 South State St., 521 Monroe St., 901 Washtenaw Ave. and 611 Stratford Drive. Eunice was a member of the Ann Arbor City Women’s Club and Garden Club. Fielding Jr. graduated from the University of Michigan, played on the football team, served during World War II, and moved to Midland where he had three children until his death in 1977.

Fielding Yost Jr. with Adolph "Germany" Schulz in 1913

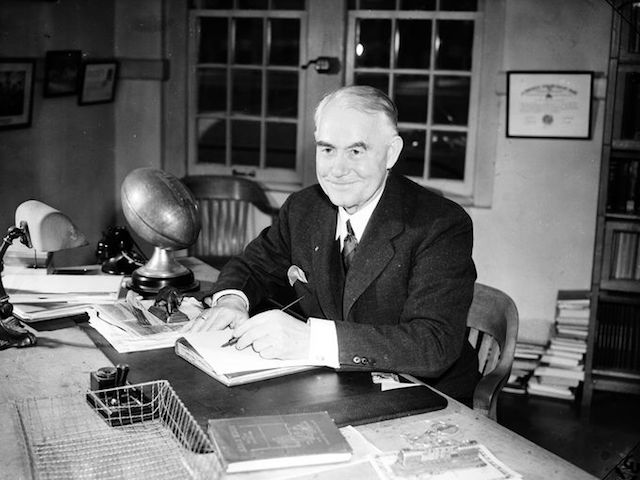

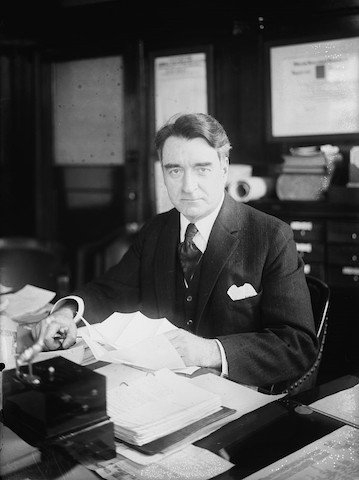

Ralph Aigler in 1935

Michigan was voted out of the Western Conference on April 14, 1907 after the Board of Control of Athletics at Michigan voted on January 13, 1907 to withdraw from the conference. The years that Michigan left the Western Conference, 1907-1917, were hard on Yost and the Michigan Football Program; they were forced to play a reduced schedule. Phil Bartelme, Yost’s Student Manager in 1902, became Michigan Athletic Director, 1909-1921; he established the Athletic Administration Building in 1912. When Michigan came back into the conference in 1917, Law Professor Ralph Aigler, 1910-1954, was named Faculty Representative, 1917-1955; Aigler became the true authority over the Michigan Athletic Program, and supervised Yost while also becoming the conference spokesman for four decades; he instituted the sanity code prohibiting athletic scholarships, and impressed on others that it is a privilege to participate in college athletics rather than a “right.” Although the Western Conference was organized in 1896, it did not have its first commissioner until 1922, John Griffith, 1922-1944.

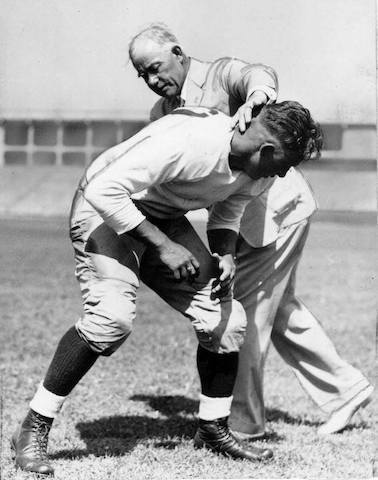

Yost and Farrell in 1912

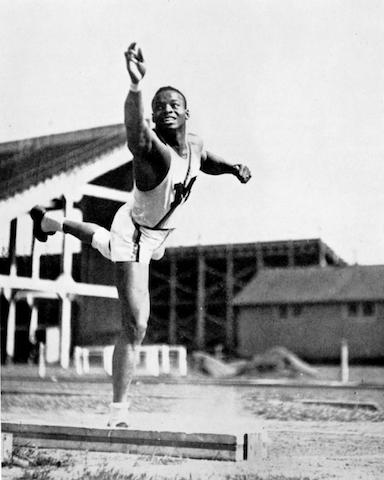

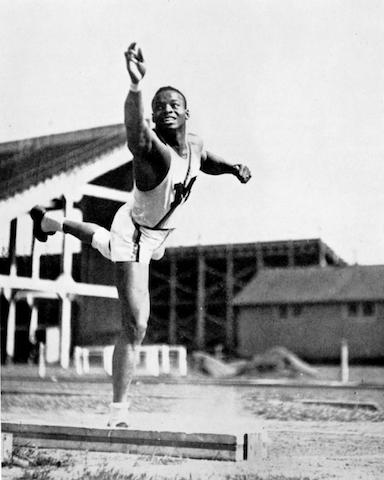

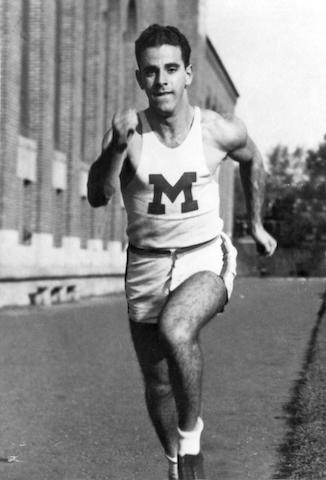

Yost hired Stephen Farrell as his trainer in 1912; Farrell was a circus performer in the 1880s and 1890s who raced against horses over 700 times while losing only 6 times. Farrell coached track, and initiated varsity indoor track (1917) and cross country (1919) with and indoor field house provided by Yost, and brought in Olympians DeHart Hubbard and Eddie Tolan while winning 10 conference championships and the 1923 NCAA Championship. Farrell brought in several negro athletes including Lorenzo Lapley from Ann Arbor High School as his first negro track athlete in 1912 followed by fellow Ann Arborite Walter Wickliffe in 1916; DeHart Hubbard was the first varsity letterman, 1923-1925, and later won a gold medal in the 1924 Olympics. Eddie Tolan, the Midnight Express, won two gold medals in the 1928 Olympics in the 100 and 200 meter sprints with world record times. Booker Brooks, 1929-1932; won the Big Ten Discus while finishing NCAA Runner-Up in the shot put.

Charles Hoyt in 1935

Yost hired Charles Hoyt in 1923 as football trainer and assistant track coach; Hoyt later became Head Track Coach in 1930, and won 14 of a possible 20 indoor and outdoor conference track championships, 1930-1939. In Hoyt’s era, another outstanding negro athlete, William Watson, won twelve conference championships in the long jump, discus and shot put, 1937-1939, and was National AAU decathlon champion in 1940 and 1943 as the 1940 Olympics were cancelled due to World War II. Watson was the first negro Captain at the University of Michigan in 1939. Both Farrell and Hoyt facilitated negro participation in track while many other Northern colleges and universities failed to do so; it was Yost’s leadership that made that happen. Yost, Farrell, and Hoyt increased negro participation in varsity athletics at Michigan placing the university far ahead of the negro participation in athletics at other Western Conference, Midwest or Northern schools; it helped change the status of negro athletes not only at Michigan, but also in the Western Conference.

William Watson in 1937

Page Fence Giants in Adrian in 1895

In Professional Sports, the Negro National League, 1920-1931 increased negro participation and interest in sports; Sherman "Jocko" Maxwell was the first Black sportscaster in 1929 at the age of 22. The league was the second effort to build professional baseball for negroes, the first was in 1878 by Bud Fowler. Adrian had a team, the Page Fence Giants, in that league, 1895-1898. Another early effort for negroes in athletics were the Harlem Globetrotters that originated in Chicago as the "Savoy Big Five" in 1926; however, they were not recognized nationally until the 1940s. Negroes were not always welcome in city parks or school playgrounds in many locales across the nation including Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti; thus, interest in athletics at that time wasn't facilitated by cities, schools, colleges, universities, etc.

Yost Field House Dedication November, 1923

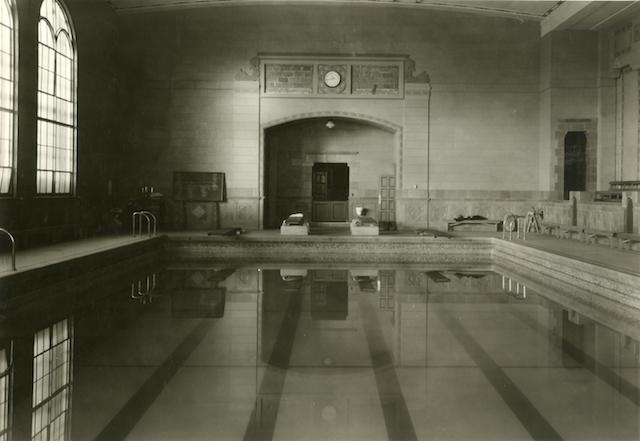

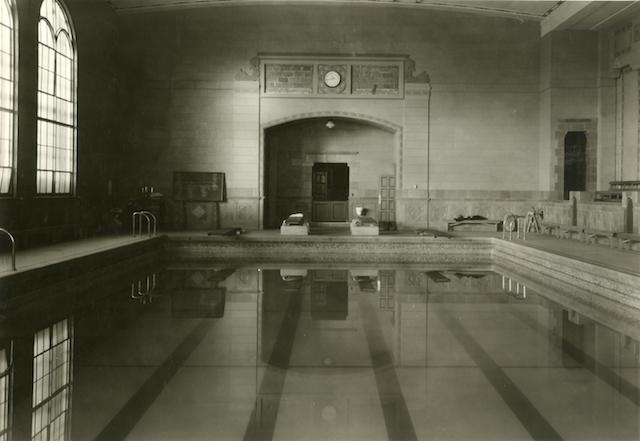

When Yost became Athletic Director in 1921, he built Yost Field House in 1923; it was the first Field House in America, and it was fitting that it was named in his honor as Yost personally supervised the entire project daily. The Field House was utilized by the Basketball, Track, Wrestling and Baseball teams, a big upgrade from Waterman Gymnasium that was built in 1894; it also hosted boxing events. Yost added an indoor pool for the Michigan Union in 1925 after hiring Matt Mann in 1923; the varsity swimming team had been using the YMCA prior to that. Due to the efforts of Mann, 1923-1955, the Wolverines hold the NCAA Record of most champions of any men's sport with 166 individual titles; Mann was selected as the 1952 Team USA Olympic Swimming Coach. He politicked for approval for Michigan Football Stadium for many years until the Board of Regents approved it in 1926; he then sold bonds to finance the project for its completion in 1927 and also supervised the project daily. Later, Yost purchased an electronic scoreboard in 1930. Yost built the Intramural Building in 1928; Elmer Mitchell, the first varsity basketball coach at Michigan was the Intramural Director, 1919-1942. Yost hired its first publicity director, Phil Pack, son of Colonel Ambrose Pack, in 1926; he served until Fritz Crisler brought in Les Etter, 1944-1968, from Minnesota.

Intramural Pool in 1930

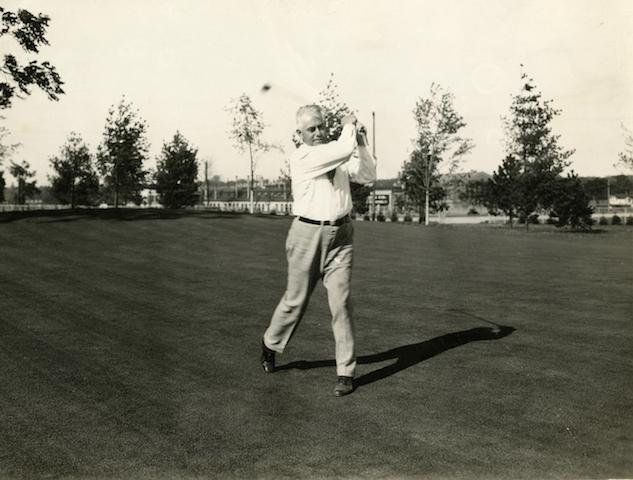

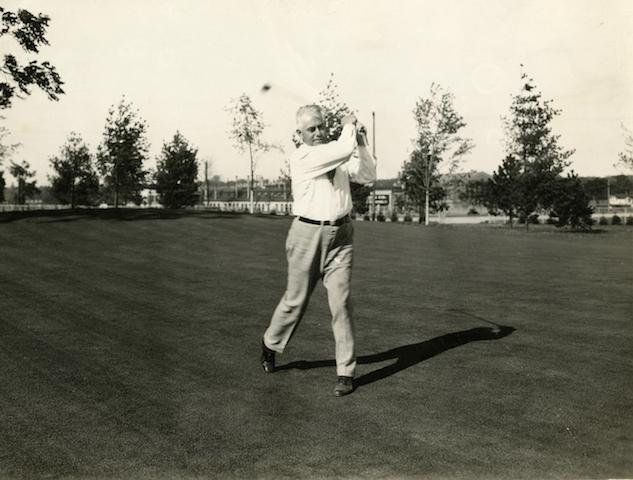

Fielding Yost on his Golf Course in 1930

Yost built the golf course in 1930 after hiring golf coach, Ray Courtright in 1927 to replace Carlton Wells who was also an English Professor, 1921-1968, and supervised that project daily as well with designer, Alister MacKenzie; Courtright coached six sports for Yost; he won eight conference and two national championships, 1927-1944. Yost hired the legendary Cliff Keen in 1925 who coached 45 seasons of wrestling including 33 seasons of football after playing for former Three-Time Wolverine All-American John Maulbetsch, 1914-1916, at Oklahoma A&M; Keen chauffeured Yost around Ann Arbor in his famed Packard which the Alumni Association purchased for him in 1927. When the NCAA Wrestling Championships began in 1928, Michigan placed 2nd at the 1928 and 1929 events, and had 2 Olympians in 1928 in 7 weight classes. Keen built the Wolverines into a wrestling power; he coached 13 conference team champions, 81 conference champions, 19 national champions and 68 All-Americans; he was the first Team USA Olympic Coach for the Wolverines in 1948. Former Wolverine football player, Ed “Don” George, was a 1928 Olympic Heavyweight who became World Professional Champion in 1930.

Cliff Keen and Fielding Yost

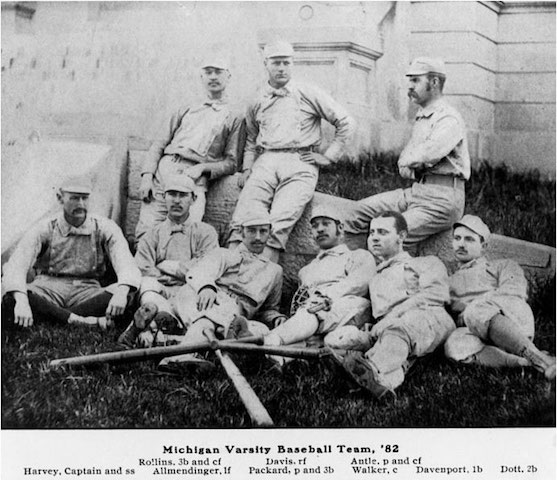

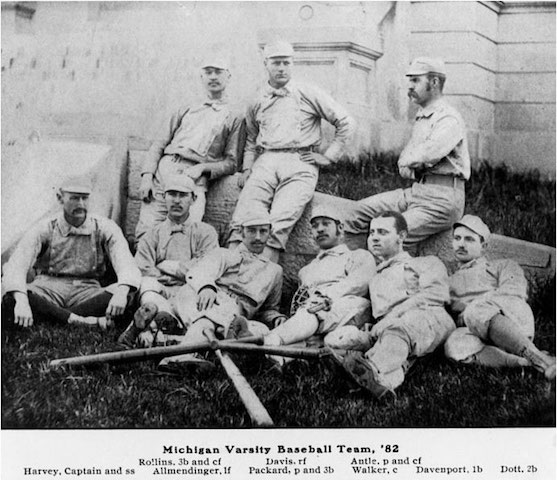

Michigan 1882 Varsity Baseball Team including Moses Walker

Yost hired Joe Barss to coach hockey, 1922-1927, and later hired, Eddie Lowrey, 1927-1944, elevated the program to varsity competition, and revamped Weinberg’s Coliseum that opened in 1909 as its home; it was utilized, 1923-1973. It was Lowrey who coached Vic Heyliger, 1935-1937; Heyliger became Michigan Hockey Coach, 1944-1957, after a four year stint at Illinois, and returned to initiate the championship tradition in hockey.

University of Michigan Coliseum at the corner of Fifth Ave. and Hill St. in 1940

Yost also added Ray Fisher in 1921 to coach baseball, 1921-1958, and he also coached football, 1921-1945; he was the winningest coach in Wolverine History until 2000 with 636 wins. Moses Fleetwood Walker was the first negro varsity athlete in college sports in 1882 when he played baseball at the University of Michigan; he was also the first negro professional baseball player, but it took until 1923 for the next negro baseball player, Rudy Ash. Yost also added varsity fencing (1927) and gymnastics (1930); however, both sports were axed in 1933 due to the depression with thousands of strikes and work stoppages. Yost’s dedication and hard-work in building Michigan’s facilities in the 1920s was unparalleled, and the envy of every college and university in America.

Baseball Grandstand in 1925

Margaret Bell and Fielding Yost at the Women's Athletic Building on Palmer Field in 1938

Yost was a “builder of men,” but also a champion for women and gender equity with his “athletics for all” approach. Yost built the Women’s Athletic Building in 1928 as well as the Intramural Building; it was the first intramural building in America, and the intramural sports program set the standard for intramural sports in America. Barbour Gymnasium had been built in 1896 after Regent Levi Barbour donated $25,000, and Palmer Field was donated by Thomas Palmer in 1910 to initiate women’s athletic facilities. Yost worked closely with Margaret Bell after she arrived on campus in 1923; she was Director of Physical Education for Women, 1923-1957. Later, Yost helped the funding women’s athletics with the Michigras that was implemented in 1902 with annual parades including the Michigan Union Parade downtown and a Penny Carnival at Yost Field House after it was built; these continued through 1965. Yost also worked closely with Myra Beach Jordan, 1902-1922; in fact, she lent her husband some of her wardrobe for the University of Michigan Opera, Michigenda, in 1908 at the Athens (Whitney) Theater. Alice Crocker Lloyd played a lead role in the 1914 Opera prior to becoming Dean of Women, 1930-1950. Yost’s football players were part of the Opera annually, and helped raise funds for the building of the Michigan Union as it transitioned from the home of Thomas Cooley in 1904 to the 1919 structure that was rebuilt. Yost's leadership in gender equity issues was unheard of in his era from an athletic leader; later, Fritz Crisler blocked the proposal of a varsity swimming team initiative led by Rosemary Mann Dawson, Matt Mann's daughter, in 1956, and even later, both Don Canham and Bo Schembechler blocked the implementation of Title IX even after women's varsity athletics were forced on them in 1973. It took the leadership of Phyllis Ocker, former Field Hockey Coach and Women's Athletic Director, and Peggy Doppes-Bradley, former Volleyball Coach and Associate Athletic Director, to fully implement Title IX and gender equity in the mid-1990s after decades of male resistance.

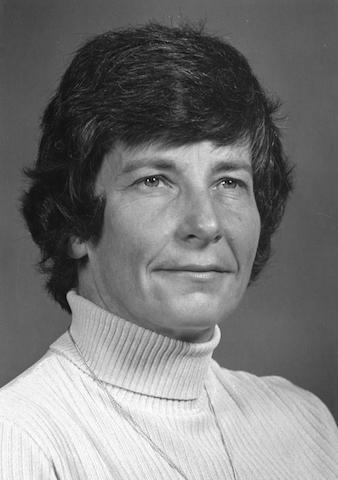

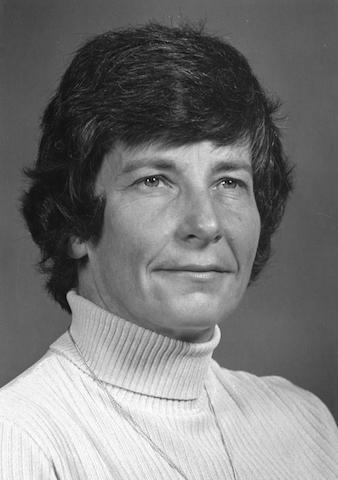

Phyllis Ocker in 1982 and Peg Doppes-Bradley in 1997

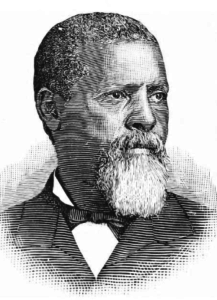

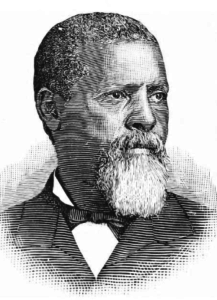

Henry P. Jacobs

When Yost arrived in Ann Arbor in 1901, the population was 14,500 with 359 negroes, 2.5% of the population; there were 231 negroes in 1870, 515 negroes in 1910, and by 1940 the number had risen to 1,200 as a result of the Great Migration that brought over 6 million negroes away from the South from 1916-1970. Systemic racial discrimination against negroes was evident for many decades prior to Yost’s arrival, and it continued during his tenure; there are many examples. The first negro religious congregation in Michigan was founded in 1836 with the Second Baptist Church in Detroit. In Ann Arbor, Union Church was established in 1854 at 504 High St., and later split into Bethel African Methodist Episcopal in 1895 at 632 North Fourth Ave. and Second Baptist Church at 216 Beakes St. which claims its start was in 1865; Ypsilanti’s Second Baptist Church was led by Henry P. Jacobs after escaping slavery in Alabama and fleeing to Canada. Jacobs was ordained in 1858, and worked at Michigan Normal College as a janitor while preaching and leading the church after the First Presbyterian Church was abandon there in 1857. Few negroes attended other Ann Arbor or Ypsilanti area churches. Minstrel shows were performed at Hill Opera House as early as 1872.

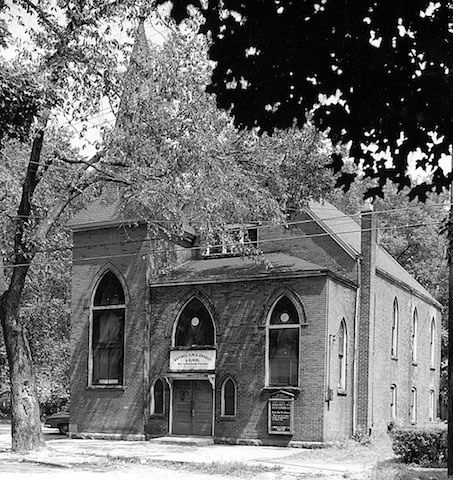

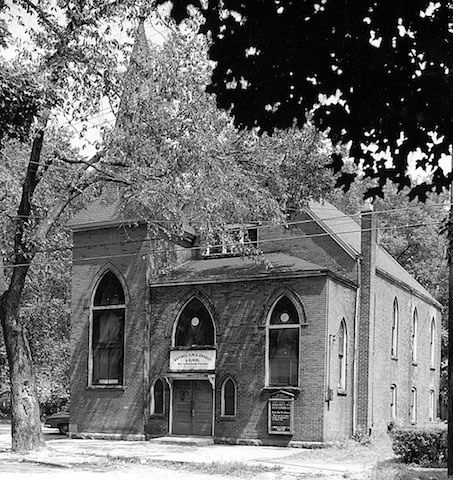

Bethel A.M.E. at 632 N. Fourth Ave. served Ann Arbor, 1895-1971

Emancipation Day, also known as Jubilee, Freedom, Liberation Day as well as Juneteenth, celebrations in both Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti as early as 1866 on various dates including July 31, August 1, 3, 11 with thousands attending; however, these events were mostly celebrated only by negroes. Some communities across the nation celebrated the event in mid-April to commemorate the death of President Abraham Lincoln; Charleston, South Carolina celebrated on January 1st, and in Tennessee it was August 8th. The Ann Arbor-Ypsilanti Interurban Railway (Ypsi-Ann) was utilized, 1891-1929, to transport people to these events as far west as Jackson and east to Detroit. Many negroes traveled to Michigan for vacation after the Idlewild Resort, the “Black Eden,” was established in 1912 in Lake County; there were 6,000 negroes who purchased 17,000 lots in the area by the mid-1920s. As Jim Crow Laws changed the political environment in the North and the South, these celebrations saw dwindling attendance by the early 1900s; however, Albion hosted a August 1, 1927 celebration with over 3,200 negroes participating. The Emancipation Proclamation was issued on September 22, 1862, and on June 19, 1865 negroes in Galveston, Texas were finally told they were free. On May 8, 2021, Ann Arbor Mayor announced that he has made Juneteenth an official city holiday; many look positively at this announcement, but the lack of honoring African-Americans by the city has been an oversight for nearly 150 years. There is currently a bill before Congress to make Juneteenth a National Holiday after 47 states now recognize it.

Jones School in 1922

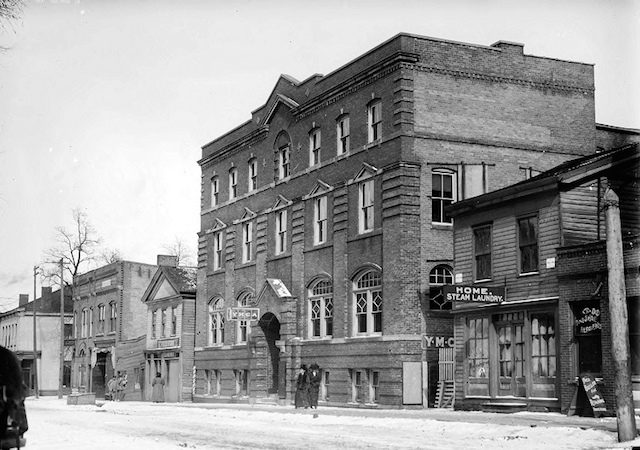

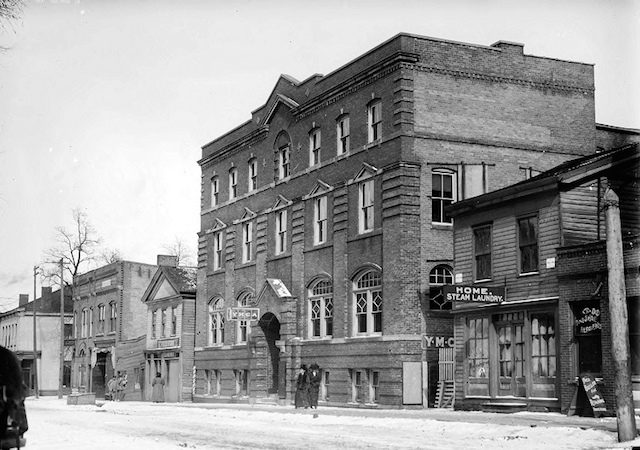

Ann Arbor YMCA in 1910

There were restaurants who refused service to negroes including the Pretzel Bell plus a restaurant in the Nickels Arcade in 1925. Barber shops and beauty parlors were segregated; students picketed the Varsity Barber Shop at 617 East William St. December, 1949 for refusing to serve negroes. Negroes were not welcome at the YMCA, a Christian organization; the first YMCA began in 1858 at the University of Michigan, and was housed at McMillan and Sackett Halls before moving to Lane Hall in 1917. The downtown YMCA was built in 1904 on North Fourth Avenue; the varsity swimming team utilized their indoor pool, 1921-1925. Redlining existed in Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti for over a century through at least the 1970s in an effort to segregate negroes into living in just certain areas of these cities. In 1931, there were 150 negro children enrolled in Ann Arbor Public Schools, 22 attended Ann Arbor High School, and 109 attended Jones School, a K-8 building; many negro students dropped out of school, and never graduated high school. Jones School was finally shut down in 1965 due to this discriminatory practice.

McMillan and Sackett Halls at the corner of State St. and East Huron St. in 1907; Jones School Baseball in 1939

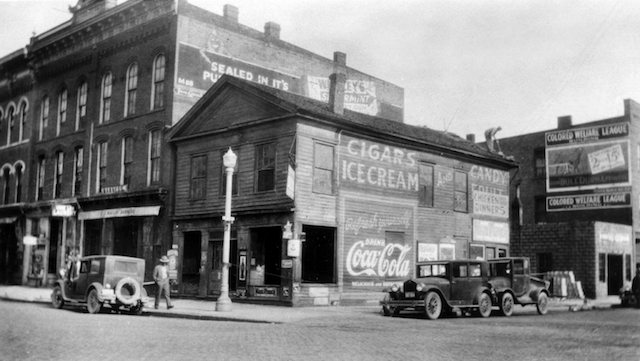

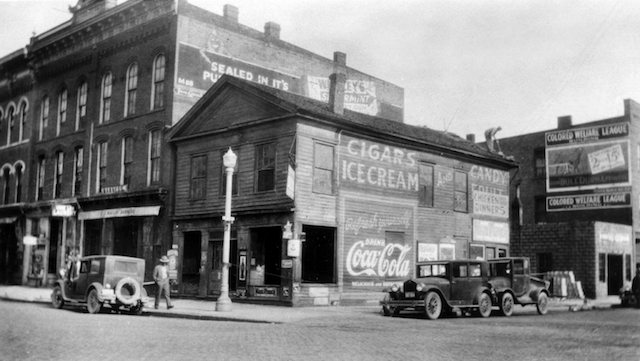

Kayser Block at the corner of Ann St. & North Fourth Ave.

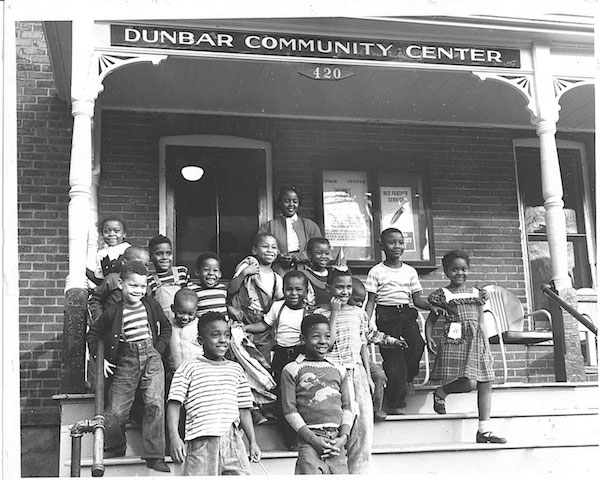

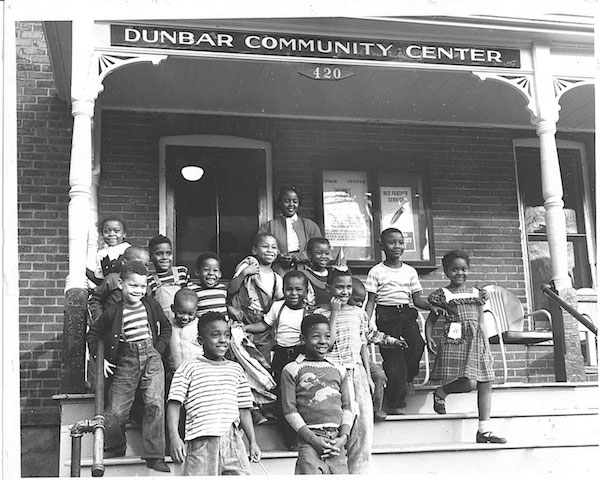

Things began to slowly change in Ann Arbor when The Colored Welfare League purchased the Kayser Block on Ann Street in 1921; University of Michigan graduate, John Ragland, became their attorney after graduation in 1938. The Dunbar Center February, 1923 to help provide short-term housing for negro workers; Yost supported the Dunbar Center in its fund-raising activities. As its membership increased from 57 to 371 members through 1936, the leadership of Douglas Williams moved the center from 1009 Catherine St. to 420 North Fourth Ave in 1937 when Homer Godfrey of Godfrey Moving & Storage donated their family home for negro social and educational activities until it was renamed the Ann Arbor Community Center after a new facility was built at 625 North Main St. in 1958. Williams was the first negro elected to the Ann Arbor School Board in 1945.

Douglas Williams in 1945

Elks Club #325 at the corner of Main and William St. in 1970; the Elks purchased the former home of William Maynard in 1910

The Elks Club #325, the largest fraternal organization in Ann Arbor with 2,700 members by 1950 in Downtown Ann Arbor on Main Street, refused to allow negroes as members since its establishment in 1895; the highly influential organization was the largest supporter of athletics in Ann Arbor, and responsible for influencing the choice of colors at Ann Arbor High School of Purple and White in 1901. As a result of the discrimination, negro men founded the Pratt Lodge #322 of the Elks in Ann Arbor in 1922 on Sunset Blvd. The Masons, Zal Gaz Grotto, Odd Fellows, Eagles, Knights of Columbus, and other fraternal organizations in the area were not welcoming negro participation. One of the first “colored” fraternal organizations in Washtenaw County was the Colored Knights of the Pythias in 1897.

Kiwanis Club picnic at Whitmore Lake in 1922

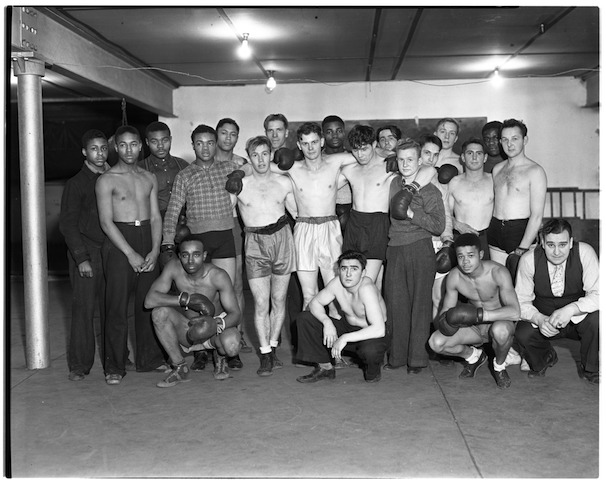

Even philanthropic organizations including the Kiwanis Clubs of Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti which were both founded in 1921 were not welcoming negro participation in activities and events. One of the first negro-owned businesses in Ann Arbor was the Ann Arbor Foundry, 1920-1972 with Charlie Baker and Tom Cook, a Jewish immigrant from Russia, at 1327 Jones Drive. Hank Griffin, a former boxer from Los Angeles, purchased a hotel at 209 North Fourth Ave. in 1908, and taught youngsters boxing; when the Ann Arbor Armory opened in 1911, and Golden Gloves Boxing was initiated in 1928, there were many boxing events held there through the end of the 1930s. The boxing competitions were one of the first integrated athletic activities in the area. Another noted negro businessman was Henry Robbins, a barber on Ann St. The book, Another Ann Arbor, was published in 2006 by Lola Jones and Carol Gibson to capture the prejudice, discrimination, and segregation history of the city as well as show the difference in culture.

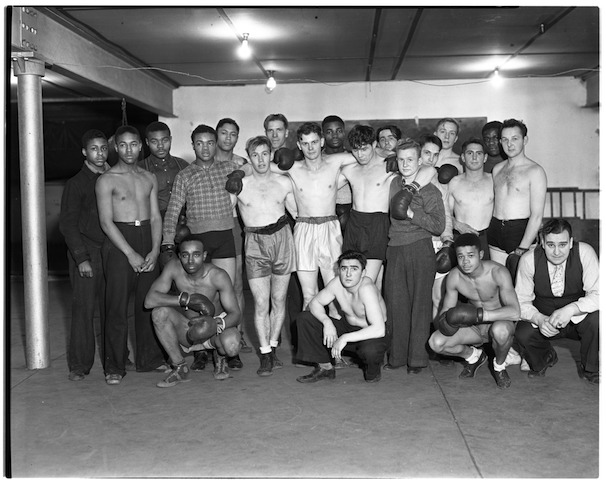

Golden Gloves boxing at the Ann Arbor Armory in 1936

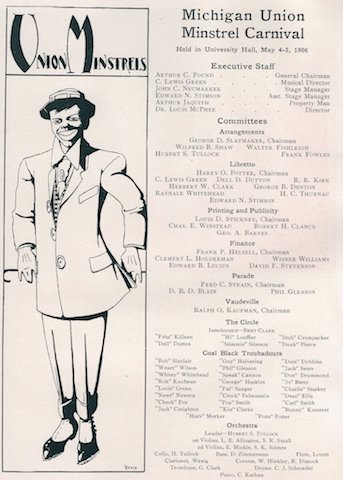

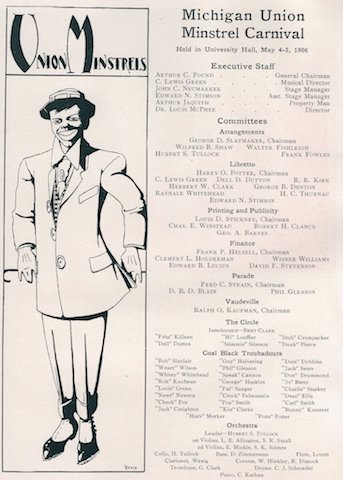

Minstrel Carnival at the University of Michigan in 1906 and Minstrel Advertising Gang in 1910

Systemic racism also existed at the University of Michigan for many decades. The first two negroes were admitted to the University of Michigan in 1868 after Samuel Codes Watson in 1853. Mary Henrietta Graham was admitted in 1876 after Michigan allowed women to enroll in 1872 even though requests for admission came from as far back as 1850. Moses Fleetwood Walker was the first negro athlete at the University of Michigan in 1882 playing baseball. The Minstrel Club was formed in 1899 (or before); they performed at the Michigan Union Opera, and also have a carnival at University Hall in 1906. Even the Michigan Glee Club which began in 1846 had minstrel performers. The University also had a terrible record in hiring negroes for staff positions since its move to Ann Arbor from Detroit in 1837; this practice continued for over a century. After Darwinism was coined in 1861 by Thomas Henry Huxley’s, On the Origin of Species; Social Darwinism became a topic of discussion in the 1870s, and the movement of eugenics began in the 1880s in America.

University of Michigan Professors in 1876

Victor Vaughn, Medical School Dean

Michigan forbid epileptics to marry in 1846; in 1893, the Michigan Home for the Feebleminded and Epileptic was established in Lapeer. Michigan was the first state to propose eugenics legislation in 1897; the law didn’t pass, but the state adopted a forced sterilization program in 1913. A majority of those sterilizations were performed at the University of Michigan Hospital with the approval of Medical Dean, Victor Vaughn, a well-known eugenics proponent. John Harvey Kellogg started the Human Betterment Foundation in 1906 at Battle Creek; they held conferences in 1914, 1915, and 1928. Kellogg later started a Fitter Families Campaign, 1928-1930. By 1928, eugenics was a topic in 376 college courses that enrolled over 20,000 students. Proponents of the foundation included Margaret Sanger, a birth control activist who began Planned Parenthood. Even W.E.B. Du Bois, Founder of the NAACP, supported eugenics. Other eugenics supporters included Presidents Teddy Roosevelt and Herbert Hoover, Inventor Alexander Graham Bell, Helen Keller, English Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, and many more.

Lester House at 909 East University in 1940

Negro women were prohibited from housing at certain University of Michigan dormitories since Newberry Hall and Martha Cook Dormitories opened in 1915 under President Harry Hutchins, 1909-1920, and later discrimination issues continued at Mosher-Jordan Hall under President Alexander Ruthven, 1929-1951. A “League House” was approved at 1102 East Ann St., 1929-1946, was approved for negro women. The first negro sorority at the University of Michigan was Delta Sigma Theta in 1921 with five women; Alpha Kappa Alpha was founded June 3, 1933 by Ruth Birth, Viola Goin, Mable James, Adele Jones, and Olive Manley. Several professors at the University of Michigan were guilty of discrimination and racial prejudice for many decades including President Clarence Little, 1925-1929; this systemic racism affected not only admissions to the university, but athletic participation, personnel and hiring practices, housing, etc. so negro students had significant difficulty in all aspects of college life. The University of Michigan Marching Band did not allow negroes to participate until Nick Falcone became band director in 1927; the band began performing in 1897. Negro students were forbidden from using the Michigan Union swimming pool and barber shop plus prohibited from participation in dances including the J-Hop which began in 1868 as the Society Hop until it ended in 1962. There have been many examples at the University of Michigan of failing to behave as “leaders and best.”

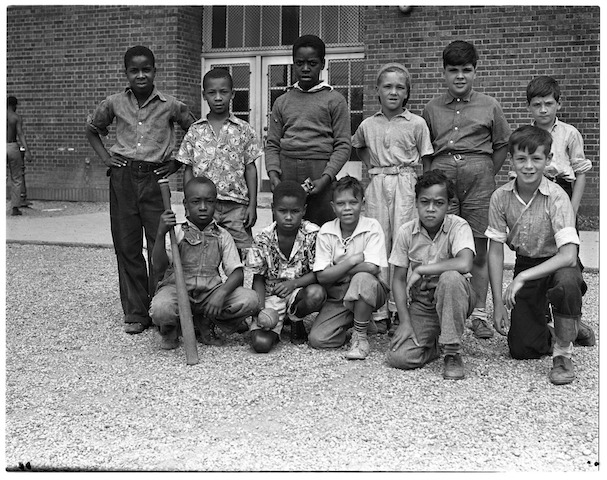

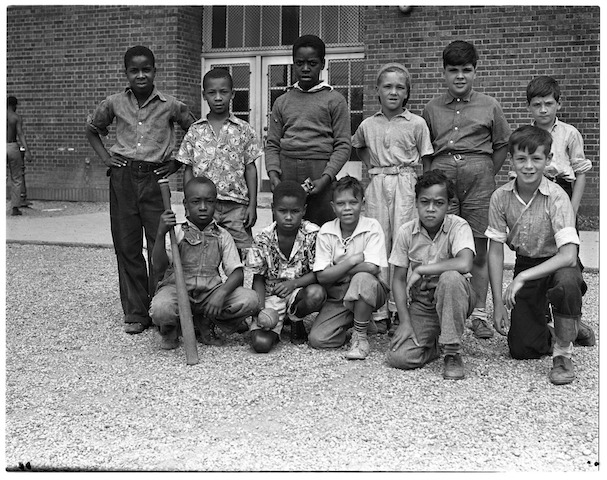

Dunbar kids in 1951

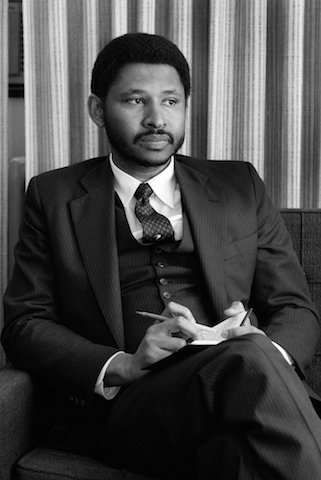

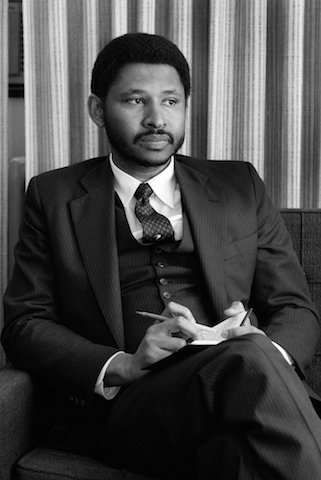

Albert Wheeler in 1957

Anti-miscegenation laws existed in America since colonial times since 1691 prohibiting interracial marriage until the Supreme Court made it illegal in 1967; Michigan outlawed the practice in 1883, but the social taboos still existed. A University of Michigan Dean of Women, Deborah Bacon, 1950-1961, advocated for refrain on interracial dating, and there were several incidents where she was called into question for her inappropriate counseling. The University of Michigan did not hire its first negro professor until Albert Wheeler in 1952; Wheeler served on the Human Rights Commission which was established in 1957, and went on to become the only African-American Mayor in the City of Ann Arbor, 1975-1978. Alvin Loving, the first negro teacher at Detroit Public Schools, was hired by the University of Michigan in 1956; Tirrel Burton was hired in 1970 as the first African-American Football Coach, and Fred Snowden plus Ken Burnley were hired for basketball and track in 1967. This pattern of discriminatory behavior and segregation at the University of Michigan for decades resulted in so much anger and frustration during the Civil Rights Movement that the Black Action Movement shut down the campus for 17 days in March, 1970. The African-American Studies Program was founded in 1970, and the Trotter House was established in 1971. The University of Michigan in 2021 has still never come close to the 10% goal of African-American students on campus since this episode in 1970.

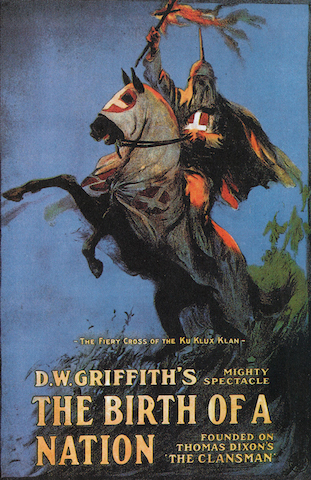

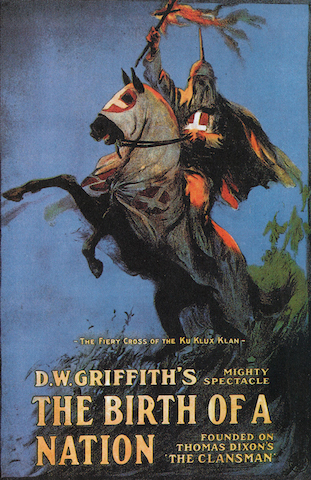

Birth of a Nation poster

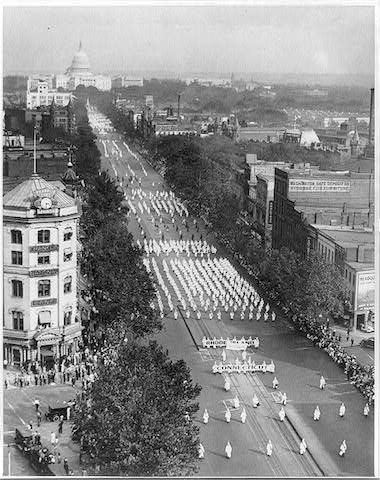

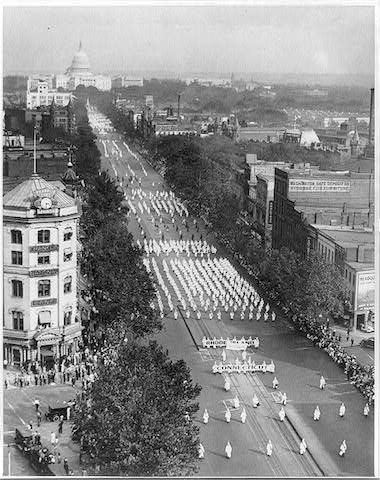

After the NAACP-National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was founded in 1909; the Detroit branch was established in 1912. The auto industry in Detroit increased the negro population by 500% between 1910 to 1920; there were 5,741 negroes in Detroit in 1910, and that zoomed to over 300,000 by 1950. Detroit was the 4th largest city in America, 1920-1950. In 1915, the film, The Birth of a Nation, intensified racial discrimination nationally, demonized negroes, and the rise of the Klu Klux Klan peaked in the United States in the 1920s with as many as 6 million members. The Klan organized marches in many cities in America throughout the 1920s including Washington, D.C. in a flagrant effort of discrimination. Racial tensions were high in Michigan during Yost’s tenure; the Detroit Riot, June 20-22, 1943 was one of many events that kept people on edge.

Klu Klux Klan March on Washington, DC in 1926 and the Grand Rapids KKK parade July, 1925

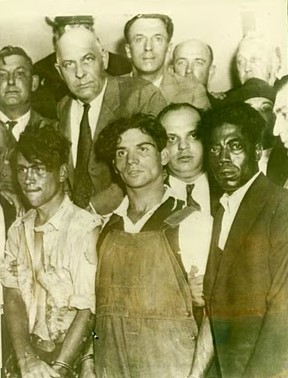

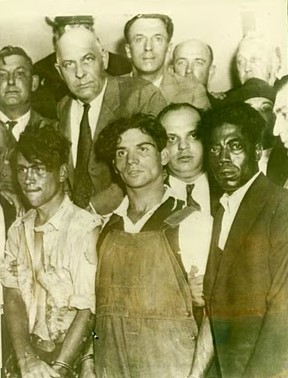

The “KKK” had a significant membership in the State of Michigan particularly in rural counties; estimates range from 265-875,000 members in the 1920s. Also, a White Supremacist group, The Black Legion, also operated throughout the Midwest during the 1930s with a membership estimated at 135,000 by the FBI. The Torch Murder Case of 1931 increased racial hostilities in Ann Arbor and Washtenaw County significantly in the early 1930s after three young men including a negro, David Blackstone, murdered four teenagers on August 11 at a local “lover’s lane;” a crowd of over 20,000 gathered at the Courthouse for a possible lynching with the National Guard called in, and the three men were tried and ushered off to prison on August 14. There was a lynching at Marion, Indiana on August 7, 1930.

Torch Murderers: Frank Oliver, Fred Smith, and David Blackstone

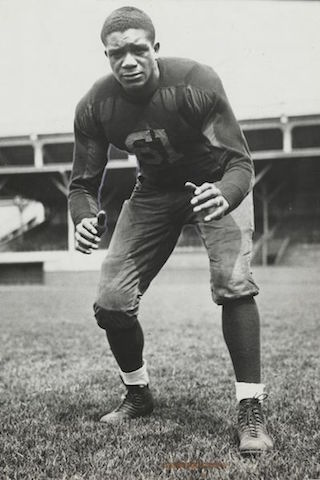

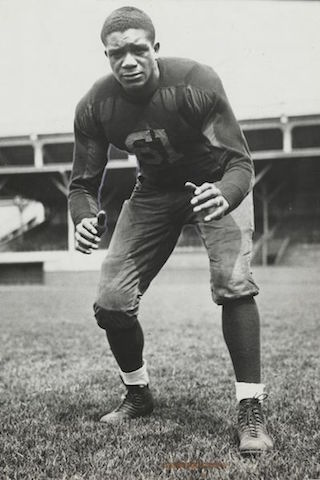

Yost had other African-Americans and minorities including Jews on his teams including Belford Lawson, Franklin Lett, Benny Friedman, John Magidson, etc.; there were other minorities who tried out for the team, but there simply were not many minority enrollees at the University of Michigan in that era. There were more foreign students enrolled than minority students at that time, and it is still the case in 2021; the International Center was founded in 1936, but there wasn't a center for African-American students until 1971. In Yost’s role as Athletic Director, he welcomed several Black students into athletics, Rudy Ash, as a varsity baseball player in 1923, Belford Lawson, DeHart Hubbard, 1923-1925, Henry Graham, as a varsity tennis player in 1928, Eddie Tolan, 1928-1931, Booker Brooks, 1929-1932 in track, Franklin Lett, Willis Ward, 1931-1935, and Julius Franks, 1940-1942, the Wolverine's first African-American All-American.

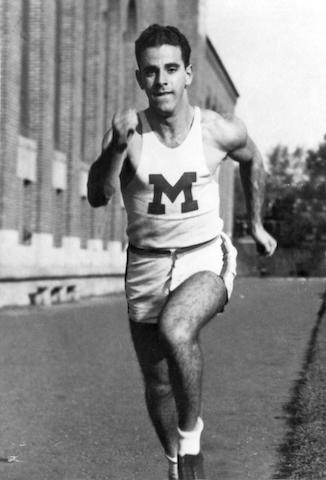

Sam Stoller

Anti-Semitism was also very strong in the 1920s and 1930s as epitomized when University of Michigan sprinter, Sam Stoller, was unable to compete in the 1936 Olympics. Father Charles Coughlin, a Catholic Priest in Royal Oak, became one of the most influential men in America as spoke out against the Klu Klux Klan with radio broadcasts of sermons as early as 1926; he had a national audience on WJR as high as 30 million from his weekly show through the 1930s, but he was forced off the air by 1940 due to his Anti-Semitic rhetoric.

Charles Coughlin

Carrie Nation speaking on State Street in 1902

Politically, one of the biggest issues of Yost’s era at Michigan included prohibition; Carrie Nation spoke in Ann Arbor in 1902, and Michigan was the first state to outlaw alcohol consumption in 1916. Joe Parker’s Saloon was the choice for many University of Michigan students at that time at Ann St. & North Fourth Ave.; the Orient was another popular venue at 109 N. Main St. Ann Arbor had outlawed any saloon or tavern above Division street near the campus. The women’s suffrage movement culminated in Michigan passing the 19th Amendment on June 10, 1919.

UofM graduates celebrate at Joe Parker's Saloon prior to Prohibition

Royal Copeland, Ann Arbor Mayor from Dexter went on to become a U.S. Senator

University of Michigan Otolaryngology Professor, Royal Copeland, 1895-1908, became mayor; he established a parks commission, spearheaded an effort to improve the environment, and the Dexter native also led the Ann Arbor School Board. Riverside Park, Island Park/Cedar Bend (1906), Arboretum (1906), West Park (1908), Burns Park, the former County Fairgrounds (1910), Wines Field (1915), Botanical Gardens (1916), etc. grew to 122 acres by 1918; Eli Gallup became Parks Commissioner, 1919-1957. Jones School was built in 1922, many negro athletic activities were held there including baseball and softball. Other University of Michigan graduates including Arthur Brown, 1903-1905, and Francis Hamilton, 1905-1907, also served as mayor; the influence of the University of Michigan on city and school affairs was significant when Yost came to the city in 1901. Hamilton donated the fountain on campus for the Class of 1869 in 1920.

Water Fountain donated by Francis Hamilton for the UofM Class of 1869 at the corner of North University near State St.

Michigan vs. Vanderbilt in 1905

The only Southern football team that Michigan scheduled during Yost’s tenure was Vanderbilt; that was mostly because Dan McGugin, a former Wolverine under Yost, 1901-1902 and assistant coach in 1903, became the Commodores Head Coach and Athletic Director, 1904-1936. McGugin and Yost married the Fite sisters, Eunice and Virginia in 1906, and the Fite sisters grew up in Nashville, Tennessee. Michigan and Vanderbilt played nine times with the Wolverines winning eight with one tie; the Commodores could only score 23 points in those nine games against Yost’s defense, 1905-1923. McGugin won 11 conference championships over his 30 seasons at Vanderbilt.

Yost at the train station with the Little Brown Jug in 1925

When Yost traveled to Battle Creek in 1928 at the invitation of John Kellogg, it was NOT to support eugenics as has been characterized in the committee’s report. Yost came to support the Family Fitness campaign launched by Kellogg, 1928-1930; Yost was an advocate for physical education. It is wrong for this committee to associate Fielding Yost with Clarence Little and his racist views in this context just as it is also inappropriate to associate Yost’s father’s service in the Civil War with the confederacy and his West Virginia upbringing in an effort to smear with reputation with inferences of racism and discrimination.

Yost made a mistake in scheduling Georgia Tech in 1934 to replace Pennsylvania. William Alexander had coached the Yellow Jackets since 1920, and were National Champions in 1928 with a Rose Bowl win in 1929; Alexander played for John Heisman, 1911-1912. The “Gentlemen’s Agreement” between Northern and Southern Football coaches for playing negro football players began in 1890; it was prior to the Plessy-Ferguson decision in 1896 which allowed the “separate, but equal” Jim Crow era to continue. This “practice” continued to plague college football even after World War II in the late 1940s. Yost was just conforming to social rules and protocol at that time.

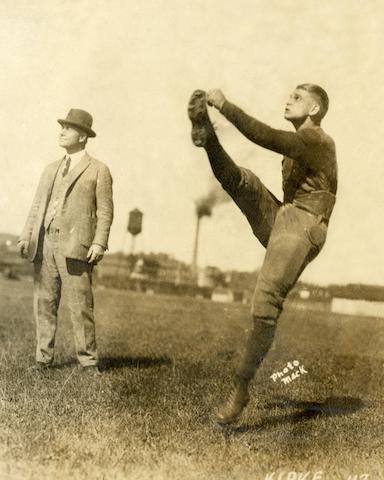

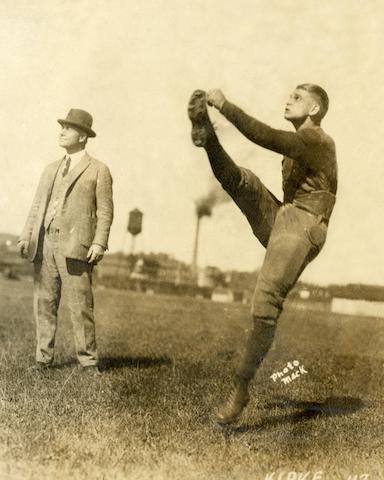

Yost watched Kipke punt in 1923

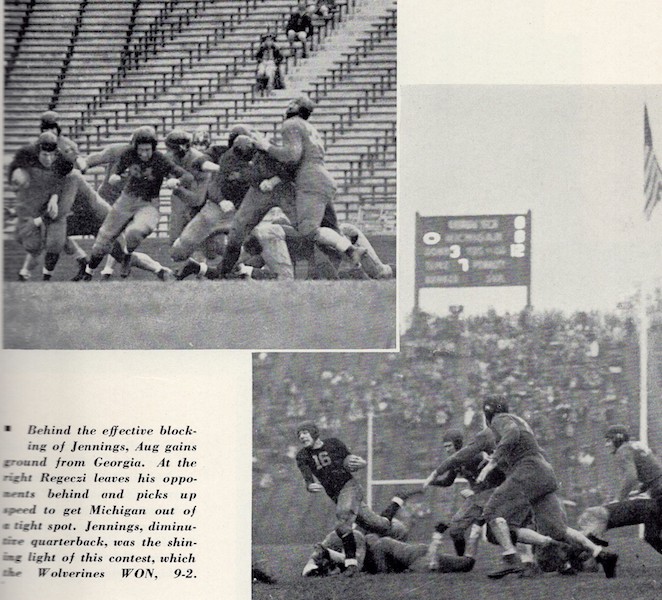

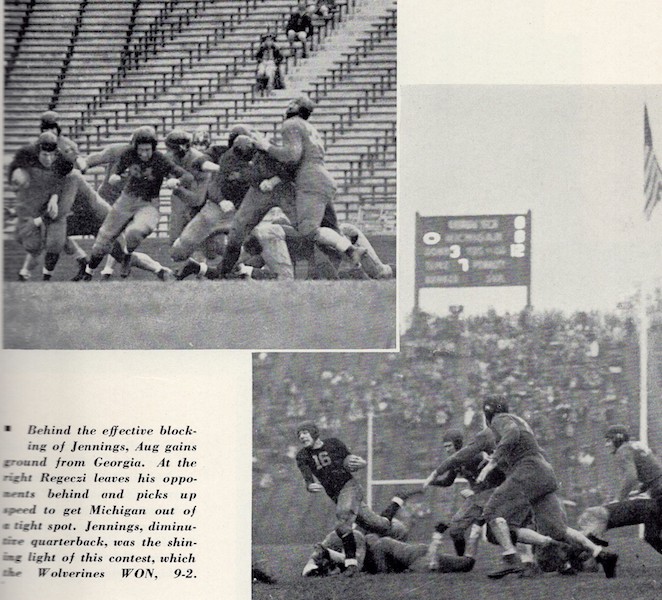

Michigan vs. Georgia Tech summary from Michiganensian Yearbook in 1935

After winning four conference championships in a row including two national championships, 1930-1933, under Coach Harry Kipke, Yost made a second mistake by prohibiting Coach Harry Kipke from playing or even dressing Willis Ward for the game on October 20, 1934 when they defeated Georgia Tech, 9-2, for their only win of the season in front of 20,901 rain-drenched fans and muddy field. Even though Ward was notified the Summer prior to the start of the season that he wouldn’t be able to play or dress for the game, the plan for secrecy failed when Michigan Daily reporter, Arthur Miller, found out about the situation, and before long the word about the benching spread throughout the student body. The student protests were warranted with a 1,500 student petition opposing his benching; some of those student protests were valid concerns for administrators at that time including Yost as students threatened to interfere with the game and create a violent scene.

Willis Ward

Ward did play the in the following week’s game with Illinois, and continued to participate in track through the 1935 season where he was an eight-time conference champion and three-time NCAA All-American (long jump, high jump, 100 yard dash). Ward defeated Jesse Owens in the 60 yard dash and 65 yard high hurdles in 1935, and tried out for the 1936 Olympics, but was unsuccessful in making the team. Ward went on to have a very successful career at Ford Motor Co. which began in 1935 due to Michigan Football supporter, Harry Bennett; Bennett had a long-term relationship with Yost and the Michigan Football Program, and provided Ford automobiles to every football coach. Ward later became a civil rights attorney and the first African-American judge in Wayne County. A Willis Ward Lounge was installed at the Michigan Union in his honor in 2015. The unfortunate event of 1934 had little long-term effect on Ward’s success athletically or professionally; in fact, that event may have helped him get the Ford job in 1935 that supported his career in law. Ward was hardly a permanent “victim” as he has been portrayed from this event.

Harry Bennett

Fielding Yost in 1938

Fielding Yost was a dedicated, hard-working, loyal coach and administrator at the University of Michigan for over 40 years, and while he wasn’t perfect and made mistakes, those mistakes shouldn’t result in his name removed from Yost Hockey Arena nor should it result in his reputation or legacy to be tarnished with improper and unfounded accusations of racism. A movement began in 1946 shortly before his death to rename Michigan Stadium in his honor; Yost put a stop to the movement citing that it should perhaps have a military tribute, and as a result the War Eagle sculpture was added in 1950 by Marshall Fredericks. The Yost Coaching Tree is well-represented with at least 77 of his former players later becoming football coaches with several also taking on the responsibilities as athletic directors. The Michiganenian Yearbook was dedicated to Yost on four occasions. Yost did not create a “culture of segregation” at the University of Michigan, it already existed, and operated.

War Eagle at the University of Michigan Football Stadium in 1950

Yost worked for five University of Michigan Presidents including James Angell, Harry Hutchins, Marion Burton, Clarence Little, and Alex Ruthven over his 40 years of service, 1901-1941. Student protests and demonstrations have been a common occurrence in Ann Arbor for decades, several erupted into violence; the 1908 student riot was a stark example of how ugly violence affected the city and the campus when over 1,000 student trashed the Star Theater after a Michigan Football player was asked to “throw” a game. Even prior to that, the “Dutch War” of 1856 pitted students at the University against Ann Arbor businesses; in 1871, a “rush” occurred when Van Amburgh Circus came to town. In 1879, only one student could enter the post office at a time after the state militia had to intervene. Another “rush” occurred at the post office in 1890. Hazing at the University of Michigan has been an epidemic from the 1867, and student violence escalated every Fall on campus with the ritual of “Black Friday” with the Frosh-Soph “games” held at Ferry Field. Michigamua was founded in 1900 as the “Hot Air Club”, and the escalation of the culture of hazing and violence on campus that has existed in Ann Arbor since 1856 through the Schlissel era for over 165 years.

Frosh Soph games conclude on Black Friday in 1924 as the students parade up State Street

Other Western Conference Schools also slowly developed negro participation in football and other varsity athletic sports. Fred Patterson played for Ohio State and George Flippin for Nebraska in 1891, Preston Eagleson at Indiana in 1893, Frank Holbrook at Iowa in 1895, Bobby Marshall at Minnesota in 1900, Gideon Smith at Michigan State in 1913, Paul Robeson at Rutgers in 1915, Jack Trice at Iowa State in 1922, William Exum at Wisconsin in 1929, Wally Triplett at Penn State in 1946, Lamar Lundy at Purdue in 1957, and Darryl Hill at Maryland in 1963. The negro players who did play football were treated rudely, and targets by many so the risks of injury were high; also, they were not accommodated by hotels or restaurants on road trips both in the North as well as the South in many locales including the famous Palmer House in Chicago.

George Wallace tried to block negro admission to the University of Alabama in 1963 in the Stand at the Schoolhouse Door

Many colleges and universities had segregational admissions policies; the first negro allowed admission at Princeton was in 1942 due to the Navy-V12 program. The University of Missouri didn't allow negro students until 1950. The desegregation of American colleges and universities was a slow process that was spearheaded by the NAACP in 1936, but it took until 1961 for a U.S. District Court Judge, William Bootle, to order the admission of two negro students, Hamilton Holmes, and Charlayne Hunter to the University of Georgia. Alabama Governor, George Wallace, stood at the door at the University of Alabama on June 11, 1963 in an effort to prevent Vivian Malone Jones from registering; it took an Executive Order from John F. Kennedy to mobilize the National Guard, and protect Jones while she registered as Wallace preached, "Segregation now, Segregation tomorrow, Segregation forever." When Wallace ran for President of the United States in 1972, he carried five states including Michigan in the Democratic Presidential Primary with nearly 51% of the state vote, and over 3.7 million votes while losing the nomination to George McGovern.

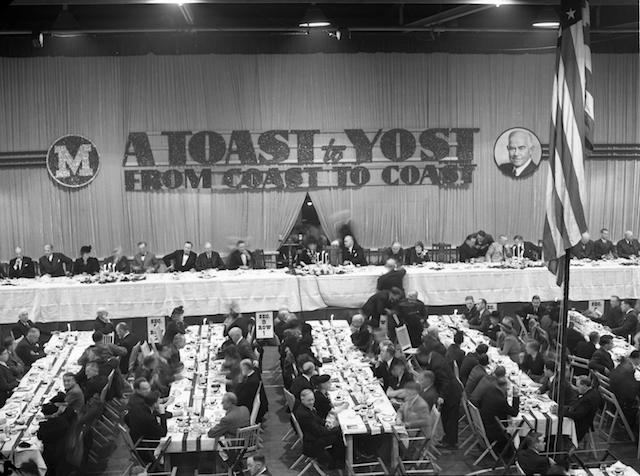

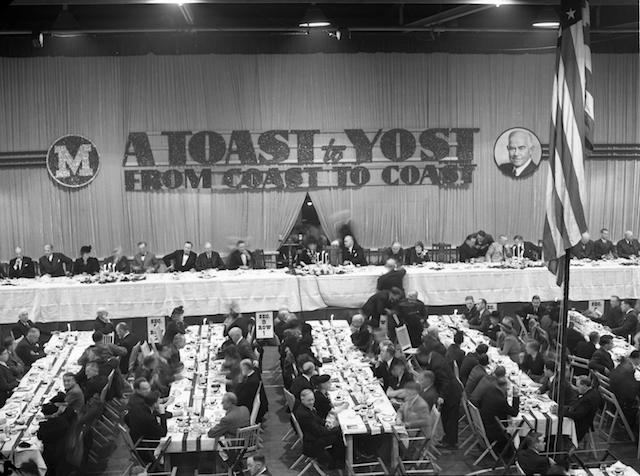

A Toast to Yost in 1940 at Waterman Gymnasium

Southern teams didn’t allow negro participation until the mid-to-late 1960, and some schools like Alabama, Auburn, Georgia, Mississippi, Clemson, and LSU stubbornly held out negro participation until the early 1970s. There were several incidents of negro football players being benched in that era: Dave Myers was benched at NYU when Georgia came to Yankee Stadium in 1929. William Bell of Ohio State against as segregated Naval Academy in 1930. Minnesota benched two negroes, Dwight Reed and Horace Bell, in a 1936 game with Texas when they won the National Championship; Reed was also held out of a 1935 game against Tulane. Basketball had the same problem; Bill Garrett of Indiana was the Big Ten’s first negro player in 1951, and Michigan’s first negro players were John Codwell and Don Eaddy also in 1951; both Codwell and Eaddy participated in baseball as well.

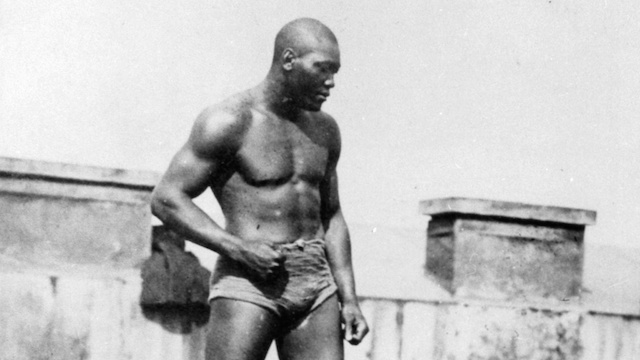

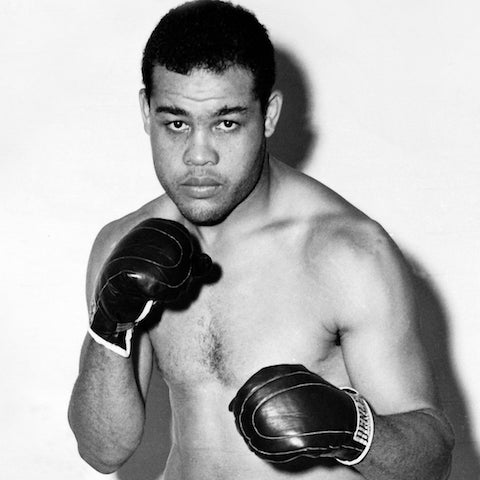

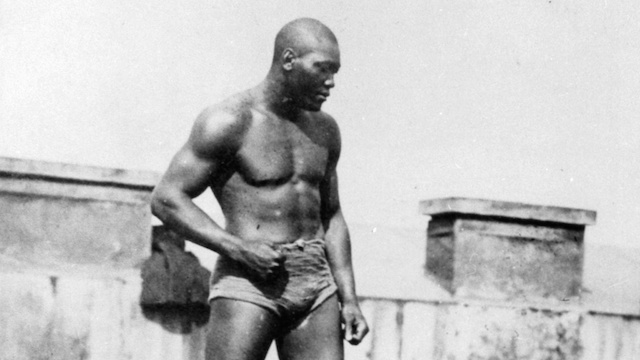

Jack Johnson

Boxer Jack Johnson, the Galveston Giant, a negro who became Heavyweight Boxing Champion in 1910, triggered riots in 50 cities in 25 states after he defeated James J. Jeffries. Later, Detroiter Joe Louis, the Brown Bomber, captured the Heavyweight Boxing Championship, 1937-1949; Louis helped break down much of the prejudice and discrimination after he defeated German Max Schmeling on June 22, 1937 in a rematch of their first fight that he lost in 1936. Louis served in the Army during World War II, and championed many across America to the cause of civil rights for negroes as a result of his achievements.

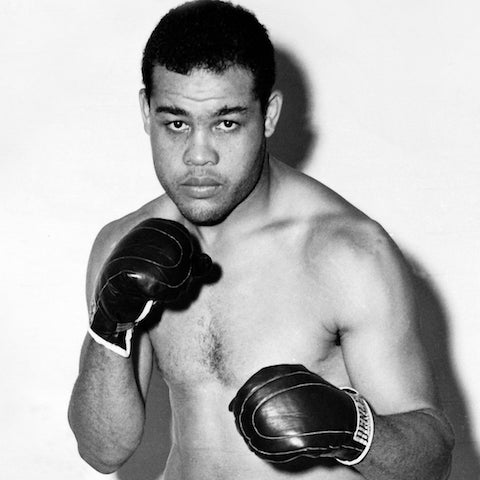

Joe Louis

President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order on June 25, 1941 prohibited racial discrimination from any government agency. President Harry Truman’s Executive Order on July 26, 1948 abolished discrimination in the United States Armed Forces; this act allowed Frederick Branch and Wesley Brown to be the first negroes to graduate from the Marine and Naval Military Academies in 1945 and 1949. There were 350,000 negroes fought in segregated united during World War I, and over 2.5 million that registered for the World War II draft with over one million serving; negroes fought in every American War since the Revolutionary War. The first statue honoring negroes in America was in 1897 at Boston for African American Civil War Soldiers, next in 1924 at Frankfort, Kentucky honoring “colored” soldiers; in 1934, a monument was erected at Philadelphia for Colored Soldiers and Sailors followed by the John Brown monument at North Elba, New York in 1935 for Enslaved African-Americans. In Michigan, no statues or monuments were dedicated until 1993 in Battle Creek for the Underground Railroad followed by the Sojourner Truth monument in 1999. Military service and these examples of political leadership were the catalysts of change for the problems of systemic racism.

Underground Railroad Monument at Battle Creek

Ray Fisher and Branch Rickey in 1959

The color barrier in professional sports was broken in baseball with Jackie Robinson’s start on April 15, 1947 for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Branch Rickey, a former University of Michigan Baseball Coach, 1910-1913, signed Robinson to a contract on August 28, 1945; Rickey was a Michigan Law School graduate in 1911. Kenny Washington had signed professional football contract only one month earlier on March 21, 1946 with the Los Angeles Rams. The “trickle down” effect of negro participation and acceptance in professional sports slowly helped college sports increase negro participation and acceptance in the next several decades.

Martin Luther King Jr. at the March on Washington in 1963

The Brown vs. Topeka Board of Education Supreme Court decision in 1954 sparked the Civil Rights Movement with brave Freedom Riders helping to bring about political change with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 following the March on Washington in 1963 led by Martin Luther King Jr. Later, the ensuing riots and violence throughout the 1960s has brought about significant social change in regards to civil rights and discrimination. The Black Lives Matter movement continues to bring civil rights and discrimination issues front and center on a daily basis since it began in 2013.

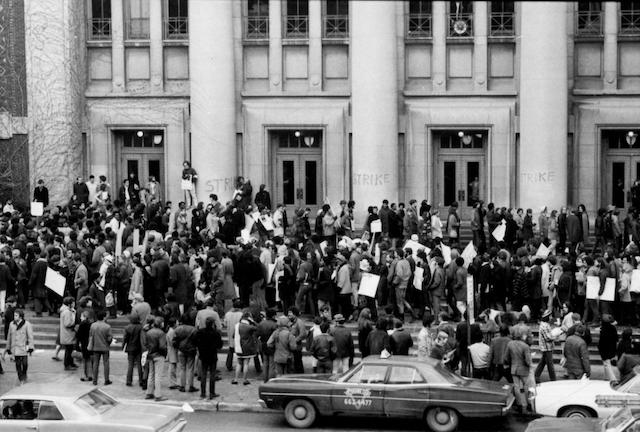

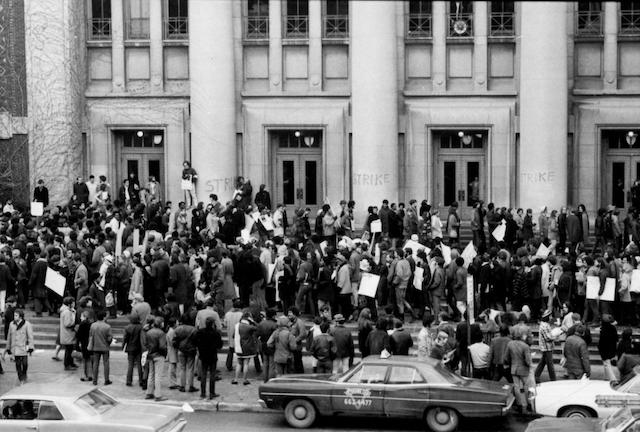

Black Action Movement at Hill Auditorium March, 1970

This committee formed by President Schlissel that has recommended Yost’s removal has not been transparent; the committee has notable academic credentials, but no athletic historian was added to the group which was a bad mistake that may have been intentional. The committee offended many including John Bacon by not being transparent about their investigation when they cited his research in his publications, but didn’t interview him; he issued a statement on his Facebook page on May 24. The committee neglected to interview John Behee who only found out about the project on May 25 after the committee issued their 36 page report on April 27; Behee does not support this committee’s recommendation. At a public university making public decisions affecting the reputation and legacy of its most valued athletic leader in its 200+ year history, it seems that transparency has been intentionally neglected.

Nellie Varner, Homer Neal and Warde Manuel

The Board of Regents of the University of Michigan should reject the President’s Committee recommendation to remove Yost’s name from Yost Ice Arena. The benching of Willis Ward nor any other historical revisionist attempts to besmirch Yost’s reputation have substantiated that he was neither a bigot, a racist or eugenicist. Yost’s body of work over 40 years of service over nearly 15,000 days to the University far outweighs the errors exposed in hindsight from the culture of systemic racism that plagued the University for over a century. According to the Michigan League for Public Policy, the State of Michigan is the third worst state in America with only 6.8% of African-American students achieving a Bachelor's Degree; the University of Michigan received a "F" grade by the University of Southern California Study in racial equity in 2018. Nellie Varner was the first African-American elected to the Board of Regents in 1981; Homer Neal became Interim President of the University of Michigan in 1996. Michigan State University named Merritt Norvell as their first African-American Athletic Director in 1995; Michigan's first African-American Athletic Director is Warde Manuel in 2016. The best way to improve civil rights and prevent discrimination at the University isn’t to destroy the legacies of the past, but to inspire stakeholders to embrace the current values that the University wants to champion. Immediately increasing the admission of African-Americans to reflect their representation in America of 13.4% of the population instead of the current 8.7% student enrollment, and implementing ideas brought forward by the Students of Color Liberation would be a great improvement. In Fall, 2020, the University of Michigan had 6,666 international students from 115 different countries enrolled; however, there were just over 2,000 Black students enrolled. Also, the hiring of African-American faculty and staff throughout the University including the Athletic Department would also be key to changing the systemic and institutional racism, segregation and discrimination that the University of Michigan has neglected to remedy throughout its history. When Mark Schlissel leaves the University of Michigan, an African-American educational leader should replace him.

Thank you for your attention!

Dave Taylor

Who is Dave Taylor?

-

A board member of the Washtenaw County Historical Society and resided in the county for 63 of 68 years

-

Retired K-12 Educator, Counselor and Administrator, 1987-2010

-

Adjunct Professor, Central Michigan University, 2006-2007

-

Graduate of Eastern Michigan University, 1978, 1990, 1993, and 1995 with Majors in Radio-TV-Film, Speech Communication and Social Studies with Minors in Psychology, History, English, and Sociology with Master’s Degrees in Educational Leadership, Guidance & Counseling and Secondary Teaching

-

NCAA Wrestling Referee, 1988-2003

-

Former Softball, Baseball Umpire and Football Referee

-

Graduate of Ann Arbor Public Schools, 1957-1970

-

University of Michigan Wrestling Donor

-

Wife, Anne K. (Cornell) Taylor, former University of Michigan Gymnastics Coach, 1974-1976, and Teacher, 1974-2007, and University of Michigan graduate, 1970 earning Master’s Degrees at the University of Michigan (1975) and Eastern Michigan University (1990)

-

Married 34 years